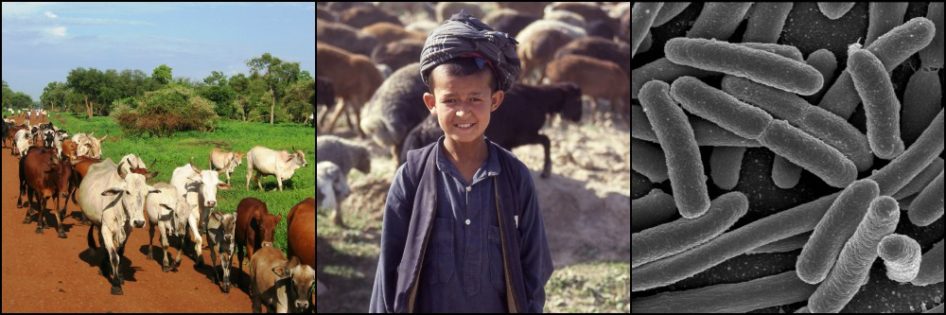

Sheep and Ankole cattle, Uganda Charles Hoots

As the world embarks on a quest to eradicate a second animal disease, peste des petits ruminants, lessons from the last successful eradication campaign will be invaluable. The stakes are high as the disease kills millions of sheep and goats, costing the world billions of dollars each year – and eradication campaigns are expensive. This post and the next look at several characteristics of this disease that make it a good candidate for such an effort.

Following in the footsteps of smallpox in humans and the scourge known as rinderpest in cattle, a sheep and goat plague known by the French name peste des petits Ruminants (PPR) is now in the crosshairs of an ambitious global eradication campaign. Lessons learned from the 5 decades-long rinderpest eradication effort make the World Organisation for Animal Health and the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organisation confident the world can be rid of PPR by 2030. They officially launched the campaign in March 2015.

It is no coincidence that PPR and rinderpest are caused by closely related viruses (also related to measles). They share certain characteristics that make them more amenable than most pathogens to elimination, yet the fight will be a difficult one, undoubtedly fraught with setbacks and surprises.

The Lessons of Rinderpest Eradication

Little known to the general public today, no animal disease has shaped human history like rinderpest. The bane of herders for centuries, it killed millions of cattle and wildlife throughout Eurasia and Africa, sparked great famines, cleared the way for conquering armies – most recently the European colonization of Africa – and prompted the creation of the world’s first veterinary schools. Its eradication, proclaimed officially in 2011, is perhaps veterinary medicine’s single most important achievement.

PPR is similarly little known, but also with huge impacts on the food security and health of those living in its shadow. It affects goats most severely, causing fever, runny nose and eyes, erosive sores in and around the mouth, diarrhea, and pneumonia. These are followed by either death or full recovery within 2 weeks of onset. The virus spreads quickly through susceptible flocks and can kill from 50% to over 90% of those affected.

PPR was first recognized during WWII in the West African country of Ivory Coast. I say “recognized” because it had certainly been around for some time before that, but was diagnosed as “rinderpest in goats” rather than as a separate entity. PPR emerged from its focus in West Africa only 30 years later, appearing over 2000 km to the east, in Sudan, in the 1970s. The 1980s saw its spread to India, followed by rapid expansion in the 1990s and 2000s to some 70 countries across most of Asia and Africa.

Global distribution of peste des petits ruminants up to 2013 OIE

There is speculation that the rapid spread of this virus is in fact the result of PPR filling the vacuum left by rinderpest. The two pathogens are so similar that sheep and goats exposed to rinderpest virus in nearby cattle were immunized against PPR. With rinderpest now gone, the sheep and goats no longer benefit from this natural immunization…

Estimates of global losses to PPR reach $2 billion/yr. Sheep and goats are commonly kept by the millions of families inhabiting the margins of agriculturally viable lands where aridity precludes growing crops and most livestock. In developing countries, sheep- and goat-rearing tend to be the domain of women and children, one of the few economic assets at their full disposal. The milk and, when sold or traded, cash and other resources the animals provide can be critical, particularly in times of drought or political instability. These demographics have both positive and negative impacts on the PPR eradication campaign.

Density of Global Sheep & Goat Populations FAO

Why PPR Can Be Eradicated

The peste des petits ruminants (PPR) eradication campaign has several things going for it.

- PPR is a deadly disease that kills an economically important livestock species. This makes people WANT to eradicate the disease – and motivation is crucial.

- Sheep and goats appear to be the only reservoirs of the disease, meaning eliminating PPR from them should lead to elimination in all other species, such as camels and affected wildlife.

- Animals that survive PPR have lifelong immunity. There is no carrier status, whereby a recovered animal still harbors the pathogen, shedding it from time to time into the environment to infect other animals.

- An effective, heat-tolerant vaccine was recently developed. Key to rinderpest eradication was a vaccine that did not require a cold chain, important in isolated and politically unstable areas where refrigeration is not practical.

- Dependable, inexpensive diagnostic tests to confirm the presence of PPR exist.

- A network of community animal health workers recruited among livestock herders and trained in basic animal disease recognition and vaccinations still exists to some extent. These workers were crucial in vaccinating against and monitoring for rinderpest, especially in war zones where outsiders could not easily travel.

Why PPR Will Be Difficult to Eradicate

Despite these advantages, PPR’s defeat also faces numerous obstacles.

- Sheep and goats are NOT cattle, so rinderpest analogies are not 100% transferrable to PPR. Cattle comprise a family’s primary economic asset and social prestige in many societies where rinderpest was prevalent. They are only occasionally traded, and slaughter for meat is exceptional. Sheep and goats, on the other hand, are sold and bartered frequently, moving between owners and villages with ease. In addition, they reproduce faster and are more numerous than cattle.

- All of this means that a greater frequency and number of vaccinations is required to eradicate PPR than was the case for rinderpest. More newborn lambs and kids provide a continuous population of naïve animals capable of spreading PPR, so they must be vaccinated before they are too old.

- PPR resembles several other diseases, complicating PPR surveillance in remote areas that have no diagnostic tests or animal health workers present. This means many false alarms and resources wasted traveling to remote areas to follow-up on disease reports. While managing a livestock health project among refugees in South Sudan recently, I was called on several occasions to investigate suspected PPR outbreaks in outlying areas of the county I worked in. These took up a lot of time and in none of the cases did PPR seem to be involved. These false alarms are partly explained by herders wanting us to visit them and bring medications and vaccines for their animals. But the problem also stems from the inability to distinguish PPR from several other diseases and tying up resources to try to figure it out.

- Many important questions about PPR epidemiology remain unanswered. For example, the assumption that wildlife are not reservoirs for the disease, and thus do not need vaccinating, is to some extent based on an educated guess from studies on captive wildlife. Similar information gaps delayed rinderpest eradication for years.

- Political will is always tenuous. Sheep and goats are generally more important to the economies of poorer countries than the wealthy ones that will foot most of the bill for the eradication campaign. True, with outbreaks now occurring in Turkey and Morocco, PPR’s appearance at Europe’s doorstep may convince these wealthy donor nations to stay the course. But PPR is still for the most part a problem of developing countries with poor veterinary infrastructure. Nevertheless, the same was true of rinderpest, and it was eradicated.

PPR eradication is achievable, but far from guaranteed. Unintended consequences are inevitable, such as the possible connection between rinderpest’s disappearance and PPR’s expansion. But, success or failure, the lessons learned from PPR eradication will further aid in designing and implementing future eradication campaigns for human and animal diseases.

I have seen PPR in 1981 in northern Kenya and the mortality in young shoats was considerable. PPR eradication will be difficult. It will be essential to understand the PPRV persistence in the camel and whether the existence of PPRV in camel has any epidemiological significance to virus persistence and transmission.