Central European wild boar (Sus scrofa). A reservoir host for African swine fever? Richard Bartz

African swine fever (ASF) is a deadly, contagious viral disease of pigs for which there is no vaccine or treatment. While primarily a scourge of sub-Saharan Africa, the disease’s recent spread into Russia and the European Union reminds us that ASF is not just a tropical disease.

Alarmingly for large swine-producing regions, from China to the EU and the United States, ASF’s behavior in the current Eastern European outbreak differs significantly from what was expected based on previous ASF outbreaks in Western Europe. These differences make expansion of the disease much more difficult to control, threatening huge economic losses to affected countries. Through October 2015, over 750,000 domestic pigs in Europe have died from or were culled to prevent the spread of the current ASF outbreak.

Recent Spread

The African swine fever virus currently circulating in Europe first appeared in swine near the Black Sea coast of Georgia in 2007. It quickly spread to neighboring Armenia and Azerbaijan and, the following year, to the Russian Federation’s Caucasus region. By 2012, ASF infections were transferred further north in Russia, to the Moscow area. A small number of outbreaks hit Ukraine in 2012 and Belarus in 2013. In 2014, the virus entered EU-member states Lithuania, Poland, Latvia, and Estonia.

The virus most commonly spreads through direct contact between an infected and a susceptible animal. It can survive for days or even weeks in an infected carcass, pig feces, or other organic material. Neither freezing nor salting and drying of contaminated pork destroys the virus.

Transport of infected pork products is a major risk for spread of ASF. It is speculated that the 2007 introduction of ASF into Georgia resulted from contaminated pork in garbage removed from an arriving ship that was fed to local pigs.

African swine fever outbreak foci in Europe 2007-2015. FAO

Poor biosecurity partly explains ASF’s expansion in Europe. Small backyard pig operations are common in much of Eastern Europe, and awareness of ASF is low. Visitors to these farms are largely unrestricted, feeding of household food waste (including pork) to the pigs is standard practice, and few barriers exist to contact between domestic pigs and potentially contaminated wild boar living nearby.

However even in those countries implementing strong biosecurity measures in their domestic swine, ASF has managed to gain a foothold and even expand. This was unexpected, and very worrisome.

African Swine Fever in Africa

ASF was first recognized in Kenya in the early 20th century when an entire herd of recently imported European breed domestic pigs died from a severe hemorrhagic disease. Subsequent investigations found that the virus causing ASF was present in wild warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus) and bushpigs (Potamochoerus larvatus) in much of sub-Saharan Africa. And it had probably been around for many years given its widespread prevalence and the mostly subclinical effects in infected wildlife and local domestic pig breeds.

Electron-microscope image of hexagonal shaped African swine fever virus

FAO, EMPRES-I

Three distinct transmission cycles (see Zika article on transmission cycles) were identified for the disease in Africa:

- A domestic cycle, in which ASF virus spreads between domestic pigs through direct contact with one another or with contaminated products or equipment;

- An enzootic cycle, in which the virus circulates between domestic swine through the bite of a species of soft tick (Ornithodoros) serving as a vector, and;

- A sylvatic cycle, in which the virus circulates between warthogs and infected soft ticks, occasionally spilling over into domestic pigs.

Out of Africa

ASF was unknown outside of Africa until 1957, when it appeared in Portugal. It lay quietly around Lisbon until 1960, when it showed up in Spain, spread to France and Italy over the coming decade, Malta in 1978, Belgium in 1985, and the Netherlands the following year. The Americas were affected, with outbreaks in Cuba, Brazil, Dominican Republic and Haiti in the 1970s. The introduction of the virus to Portugal and the Americas was likely the result of feeding contaminated waste from international ships or aircraft to pigs. Studies showed that all of the European and American ASF viruses were identical and almost certainly from a single source.

With the exception of the Italian island of Sardinia and southwest portions of Spain, these incursions of ASF were short-lived following aggressive control and prevention measures in the concerned countries. But the situation in Spain proved tricky. When an eradication campaign began in 1985, ASF swiftly retreated to the southwest corner of the country, from where it proved very difficult to eliminate.

This part of Spain at the time featured numerous risk factors for ASF: poor biosecurity, unregulated transport of swine, garbage-feeding in numerous backyard pig facilities, and poorly controlled wild boar populations. In addition, the area harbored the soft tick species Ornithodoros erraticus, which proved to be a competent vector and long-term reservoir for ASF virus. This tick frequents bird nests, mammal burrows, and the underside of rocks, all in close proximity to swine.

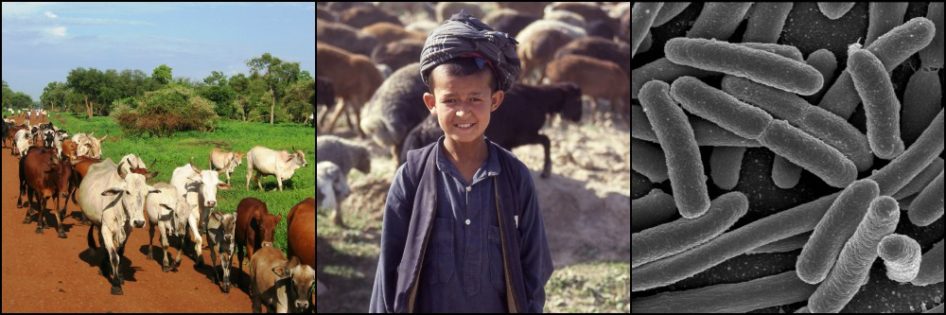

Backyard pigs kept under low biosecurity conditions are still common in much of the world. The risk of ASF transmission to these pigs from infected wild boar, people visiting from infected farms, or feeding of contaminated waste meat is high relative to industrial farms with strong biosecurity. Alison Phillips

Only in 1995 was this expensive campaign declared a success and mainland Europe was cleared of ASF. Subsequent testing in southwest Spain failed to find any ASF virus in wild boar, whereas previously 10% of wild boar living near to ASF-affected domestic pig herds were positive for the virus.

This led to the logical assumption that wild boar populations alone cannot maintain ASF virus for long periods, and that eliminating the virus from the domestic pig population would soon lead to it dying out in wild boar too (unlike with the warthog and bushpig reservoirs in East and Southern Africa). This belief would soon be proven wrong in Eastern Europe.

False assumptions

In the early years after African swine fever’s 2007 arrival in Georgia and its neighbors, the virus appeared to spread predominantly through the transport of domestic pigs and their products. On reaching southern Russia, the pathogen entered the wild boar population on a large scale. Yet the subsequent spread to pig farms in northern Russia in 2011-12 was most likely, again, through transport of domestic pigs from the south.

Similar movement of domestic pigs or their products from Russia or Belarus was considered the highest risk for introduction of ASF to the European Union. Yet the 2014 arrival of disease into the EU ended up being the work of wild boars. Molecular studies showed three independent introductions of ASF virus into Poland as part of the current outbreak, probably from wild boar in neighboring Belarus. And over 90% of reported ASF disease events in the EU are in wild boar. Less than 10% are in domestic pigs, and all of these have been within 30 km of the border with either Belarus or Russia. Infected wild boar contaminate the surrounding area with feces, urine, and blood, and farmers infect their pigs by feeding them grass collected from these areas.

With up to 50 domestic pigs per square kilometer, parts of Poland have the highest density of low biosecurity backyard pig farms among the four affected EU-member states (Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Poland). When ASF reached here in February 2014, many speculated that it would spread rapidly through the wild boar population, killing a large number of them, and quickly burn itself out when no new susceptible hosts were available. Strong biosecurity in domestic pig farms, along with immediate isolation and culling of affected domestic herds, would in theory prevent spread to the larger swine industry as ASF swept through before disappearing for good. This was to a large extent based on observations from ASF epidemiology in Western Europe from the 1960s-90s.

Density of domestic pigs kept in low biosecurity facilities in Europe/Western Asia. Such facilities are at highest risk of ASF infection and are concentrated in Eastern Europe (Poland, western Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, eastern Slovenia, Hungary, Poland, and Macedonia). FAO

Yet the disease had some surprises in store. ASF virus spread steadily but NOT rapidly in the EU, even in areas with large wild boar populations in Poland and Latvia. The particular form of the virus in Europe today is highly virulent and kills a high percentage of the swine it infects. But it turns out to spread surprisingly slowly from one animal to another, even within a single pig herd in many cases. That was the first surprise.

The slow geographic expansion of ASF is at least partly explained by wild boar social behavior. Only about 30% of wild boar in eastern Poland, for example, ever venture more than 2 km from the home range in which they were born. The small percentage of wild boar that do leave their home range (less than 10%) do not go more than 30 km away. And contact between different family groups is limited.

Another surprise stems from the fact that ASF virus persists in the wild boar population of the affected EU states, even in the absence of much spillover of disease from domestic pigs. This contradicts the predictions from Western Europe that elimination in domestic pigs would result in elimination from the wild boar population too. Effective prevention measures largely kept the virus out of domestic pigs in the Eastern European EU member states, even on backyard farms. Yet the pathogen remained in the wild.

Density of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Europe/Western Asia. The confluence of high densities of wild boar and low biosecurity swine facilities increases the risk of ASF spread to domestic pigs. This is most notable in Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, Poland. FAO

That is bad news for the large parts of Eastern Europe harboring high densities of wild boar. The virus could become enzootic (i.e. established and maintained in one or more animal species without the need for an outside source of infection; the non-human equivalent of endemic) there, with a transmission cycle similar to Africa’s rather than that in Western Europe previously: wild boar serving as maintenance reservoirs for the virus while domestic pigs become occasional spillover hosts leading to expensive outbreaks and interruption to trade.

Fortunately, the soft tick species that acted as an ASF virus vector in southwest Spain has not been found in Eastern or Central Europe, and no other vector species have been identified there.

Repercussions

As so often happens, the 2014 African swine fever virus in Europe clearly behaves differently from that of earlier outbreaks in Western Europe, let alone in sub-Saharan Africa. ASF is not a high priority in many countries, perhaps because it is not a zoonotic disease, many affected countries do not export pigs or pork products, and the extent of the problem is not appreciated as many backyard farmers do not recognize or report the disease to authorities. Russia and EU countries have been quick to notify their trading partners of disease progression in their countries, via reporting to the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). But not all countries are so diligent. Some take over six months to report new cases.

Nevertheless, the economic repercussions of ASF are substantial in lost trade, dead or culled animals, and the heavy costs of monitoring, prevention, and control measures. Georgia and Armenia each lost well over half of their entire domestic pig population as a result of ASF. In the Russian Federation, total losses due to ASF in the four years from 2008 to 2011 alone are estimated at the equivalent of US $240 million. And the virus is probably there to stay for the foreseeable future, despite new regulations such as microchip requirements in commercial swine.

Neighboring countries will be at constant risk of ASF until the virus is controlled in Belarus and Russia. And that will not be simple given the new epidemiology of the disease in these regions.

References

Bosch J, Rodriguez A, et al. Update on the Risk of Introduction of African Swine Fever by Wild Boar into Disease-Free European Union Countries. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2016.

Mur L, Boadella M, et al. Monitoring of African Swine Fever in the Wild Boar Population of the Most Recent Endemic Area of Spain. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2012; 59.

Pietschmann J, Mur L, et al. African swine fever virus transmission cycles in Central Europe: Evaluation of wild boar-soft tick contacts through detection of antibodies against Ornithodoros erraticus saliva antigen. BMC Veterinary Research. 2016 Jan; 12(1).

Sánchez-Vizcaino JM, Mur L, and Martinez-López B. African swine fever (ASF): Five years around Europe. Veterinary Microbiology. 2013 Jul; 165(1-2): 45-50.

Śmietanka K, Woźniakowski G, et al. African Swine Fever Epidemic, Poland, 2014-2015. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2016 Jul; 22(7).