Cattle fever ticks were for the most part eliminated from the United States over 70 years ago. Now they are back and spreading well beyond the buffer zone established along the Texas-Mexico border designed to prevent their return. Techniques that succeeded in ridding the US of these dreaded ticks decades ago are no longer as effective at killing or even containing them.

The two tick species Rhipicephalus annulatus and R. microplus both reduce milk and meat production in cattle through blood loss, and decrease the value of skins from slaughtered animals. But more importantly, they also act as vectors of the deadly pathogens that cause babesiosis, or cattle fever, one of the more important arthropod-borne disease of cattle worldwide.

Rhipicephalus spp. life stages; left to right: larva, nymph, adult engorged female. USDA-APHIS

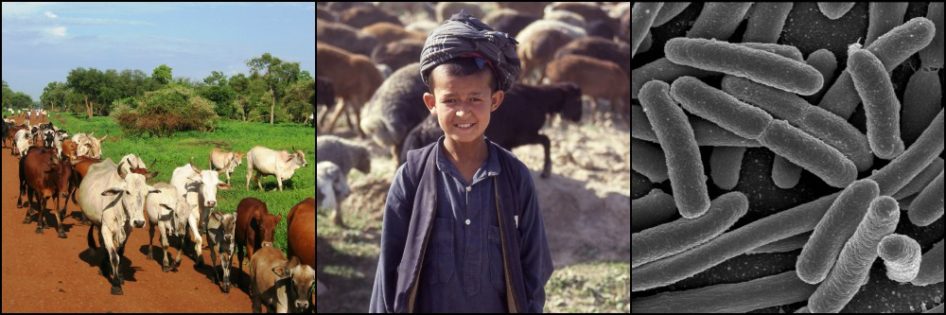

Referred to collectively as cattle fever ticks, the natural homeland of R. annulatus is the Mediterranean basin, the Near East, and southern Russia, while that of R. microplus is the Indian subcontinent. The former, at least, arrived in the Americas on livestock brought by European colonists in the 16th century, spreading through much of South, Central, and North America as far north as Virginia.

Both tick species feed and molt from larvae to nymphs to adults on a single host animal. They prefer cattle, but can also feed on a number of other livestock and equine species, and, critically, on various wildlife species.

Life cycle of one-host tick: An engorged female drops to the ground and releases ca. 3000 eggs before dying. Female ticks may feed on a host for up to 4 weeks before dropping off to lay eggs and die, sometimes very distant from where they hitched the ride originally. This helps spread the ticks (“Boophilus” is the old genus name for Rhipicephalus microplus). Queensland Govt Dept Ag & Fisheries

Cattle Fever

Both species of cattle fever tick (CFT) can harbor the protozoan organisms that cause babesiosis in cattle (and sometimes in people): Babesia bovis and B. bigemina. These organisms break down the membranes surrounding red blood cells, causing them to burst. This results in anemia, fever, weight loss and, in more serious cases, the appearance of blood in the urine. In naïve herds, up to 90% of the infected adult cattle may perish if not treated early in the disease process.

Discovery of these pathogens and their transmission by certain tick species in the 1890s was the first definitive connection established between an infectious disease and an arthropod vector, opening the way for critical discoveries in malaria, yellow fever, and trypanosomosis (sleeping sickness) research in the coming decades.

Red blood cells of a cow infected with Babesia bovis (arrow). Alan R. Walker

CFT ticks acquire the Babesia organisms from the blood of an infected host. Since an individual CFT generally only takes a blood meal from one host in their lifetime, they do not transmit the pathogens to another susceptible animal. Instead the mother passes the organisms to her eggs, and the infection persists as the eggs hatch. B. bovis develops for a few days before it is ready to be transmitted by the larvae, while B. bigemina is more readily transmitted to a host a few days later, when the tick reaches the nymph or adult stages.

Adult cattle suffer more severely from babesiosis. The young, up to 9 months old or so, tend to show few if any signs when infected. But they become immunized against the disease even in adulthood.

The downside is that many of these calves continue to harbor the Babesia pathogens for years. Periodically these carriers will have enough organisms in their bloodstream to infect a feeding CFT tick, maintaining the cycle of disease.

In the enzootic situation described above (i.e. where Babesia pathogens circulate over long periods within a cattle population), a balance is forged. Most cattle are infected as calves and are immune to the severe disease that can occur in adults. Livestock owners may not even know the Babesia pathogens are ubiquitous in their herds.

This can be an acceptable trade-off in many cases. But in the United States of the 19th and into the 20th century, cattle movements from or into Babesia-ridden areas frequently spread the pathogen and its tick vectors to naïve herds, resulting in huge losses (see sidebar).

Once the tick-Babesia relationship was understood, a concerted effort was made to eliminate the disease from the US.

The Eradication Campaign

Without cattle fever ticks, cattle fever will not survive. That was the foundation of the campaign formulated in 1906 to eliminate CFTs from the 14 US states infested with them.

Based on the ticks’ behavior, a two-pronged strategy was, and still is, employed:

- Pasture vacation involved the removal of all livestock and equines from a given area of land for up to 9 months. In the absence of livestock hosts, the tick larvae that hatched from eggs on that land found no hosts, dried out, and died after 3-6 months.

- The animals removed from the vacated pasture were treated thoroughly with a tick-killing acaricide every 1-2 weeks until no more CFTs were found on them.

Not everyone was initially supportive of the project. The strategy required livestock owners to have an accurate inventory of their herds, good fencing to prevent animals “escaping” back onto the vacated pastures, and easy access to the vacated cattle every week or two for tick treatments.

Some thought the campaign cost too much (it was funded jointly by federal, state, local, and private interests), doubted it would succeed, and felt that too many animals were injured from such frequent handling.

Cattle passing through a tick treatment bath (“dip”) in south Texas. This is the most effective way to ensure whole-body application of acaricide to the animals. USDA ARS

Nevertheless, the program proved hugely successful and by 1943 CFT ticks were gone from all but peninsular Florida and a narrow buffer zone established along most of the Texas-Mexico border.

Unexpected Complications

All went smoothly until the CFT elimination campaign reached central Florida. Here the pasture vacation and tick treatment strategy that worked so effectively elsewhere began to fail. In 1931, livestock owners and authorities near Orlando (40 years before Walt Disney World opened) began to notice that many cattle repeatedly treated with acaricide still harbored Rhipicephalus microplus long after the tick should have been gone.

Hunting season inspections revealed the presence of the tick on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the surrounding area. This raised the alarm that the wide-ranging white-tailed deer, and possibly other wildlife species, may be able to host and sustain CFT tick populations in the absence of livestock or equine hosts.

Male white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) . Jerry Segraves

To protect against this possibility, in 1938 pasture vacation and acaricide treatment were combined with culling of white-tailed deer in central Florida. In addition, an 80-mile long electrified fence was extended across southern Florida to prevent deer living in the inaccessible Everglades wetlands from moving into cattle areas.

This strategy proved quickly successful, and in 1943 no CFTs were found in Florida livestock. Curiously, small outbreaks of the ticks recurred in Florida on five different occasions over the next 15 years. It was suspected that deer acting as reservoirs had spread the ticks to cattle, but this was never confirmed and no more CFTs were found in Florida after 1960.

Mounting Frustrations

With CFT ticks virtually gone from every state, the US established a buffer zone in 1938 along the Texas-Mexico border, called the Permanent Tick Quarantine Zone. Running parallel to the Río Grande river for 580 miles today, this narrow strip ranges from 10 miles wide to as little as 125 yards wide in places.

The zone is carefully monitored by mounted US Department of Agriculture employees called “tick riders.” These look for the presence of CFT ticks hitchhiking on stray horses or livestock crossing into Texas from Mexico, where CFTs are still abundant.

CFT-infested animals were discovered every year, and in 1965 the US government constructed a 4.5-foot high double fence through the buffer zone. The fences were 15 feet apart and the area around them was defoliated to eliminate suitable habitat for tick eggs or their newly hatched larvae.

As occurs frequently with such long stretches of fencing to keep out animals, the results were less than hoped for. Livestock and potential wildlife hosts of CFTs continued to make or find weaknesses in the barrier, crossing often.

South Texas habitat near the Río Grande river. The double fence built in 1965 can be seen (at left and right of photo), now fallen into disuse. USDA-APHIS

CFT incursions into the Texas buffer zone had been detected and controlled with few problems for the first 30 years of its existence. But in 1968, signs of trouble surfaced. CFT ticks began showing up frequently on white-tailed deer in various parts of south Texas, just as they had in Florida earlier.

The number of ranches reported with CFT infestations increased significantly in the early 1970s, until finally coming under control in 1978.

By the mid-1970s, the inevitable began to happen: ranches north of the town of Laredo were no longer getting rid of CFTs after pasture vacation and systematic treatment of their livestock and equines for ticks. A closer look showed CFT-infested white-tailed deer frequenting these “vacated” pastures, thereby maintaining the tick populations while the livestock were gone.

This map of the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) range demonstrates the high density of deer in central Florida that forced a rethinking of the cattle fever tick elimination campaign in the 1930s. This map is from 1988, and population densities are probably higher in most places today, including in south Texas. The deer in Florida have made a comeback since culling stopped after CFTs were eliminated there.

The failures of pasture vacation progressed slowly. But by the late 1990s it was clear that though cattle may be the preferred host of CFTs, both species of tick could survive and spread on white-tailed deer and certain exotic wildlife species found in south Texas and northern Mexico, in particular the nilgai antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus) and Eurasian red deer (Cervus elaphus).

The situation went from bad to worse. By 1999, CFTs were frequently escaping the heavily monitored buffer zone and appearing in formerly CFT-free parts of south Texas. In the coming years some pastures vacated of livestock and equines for up to 10 consecutive years were found to still contain CFTs.

Male nilgai antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus). Nilgai were introduced to Texas from South Asia in the late 1920s. They number more than 38,000 today and are a popular prey for game hunters. Lisa Purcell

The Quest for Innovative Solutions

With hunting so important to the Texas economy and the likelihood of a public outcry, culling of the deer and antelope in the area was put aside. A strategy of treating deer with ivermectin-medicated corn at special feeders was adopted instead, along with acaricide-infused head- and back-rubs made attractive with bait. A cattle vaccine to kill biting ticks is also being introduced, but it will take time to assess its value.

A white-tailed deer buck at a head-rub site. Acaricide is applied to the head, neck, and ears of the deer as it feeds. Wayne Ryan

Knowing that ticks remained on their vacated pastures, ranchers began returning their cattle to these pastures at the height of tick season, when any tick larvae there from deer infestations would latch on to the cattle. These were then promptly removed from the pastures and the ticks killed with thorough acaricide treatment in a technique referred to as “sponging up.”

Many long-infested pastures were cleared of ticks with these new approaches. But the ticks were not to be outdone. New quarantine areas were expanded beyond the buffer zone. By 2009, tick infestations were declared on 146 different premises in Texas, double the number reported just five years before, and over half of which were located outside the buffer zone.

Disturbingly, in December 2016 CFTs were discovered on Texas ranches over 100 miles from the border region.

Ongoing cattle fever tick outbreaks in Texas as of April 30, 2017. The red line along the border with Mexico marks the northern boundary of the Permanent Tick Quarantine Zone, often referred to as the “buffer zone.” Note the infestations in Live Oak County, far to the north of the buffer zone. This outbreak was discovered in December 2016 and has caused great concern. It was likely due to the transport of a tick-infested livestock animal(s) from the buffer zone without detection, but this has not been confirmed.

Pathogenic Babesia organisms have not been found in any of the cattle or ticks in Texas so far, but allowing the CFTs to spread at this point is not an option. Over a quarter of beef cattle in the US spend part of their lives in Texas and the recolonization of its previous range in the southern US by CFT ticks could result in costs estimated at up to US $1 billion annually.

The situation has become serious as tick control strategies that proved effective for 80 years are no longer working.

What has happened? Is south Texas so different today than it was just a few decades ago, that these ticks are able to thrive and survive an onslaught of efforts to kill them?

The answer turns out to be yes. See the upcoming post on the confluence of factors that prepared the way for CFTs’ return.

RESOURCES

Bock RE, Jackson LA, et al. Babesiosis of cattle. Parasitology. 2004 Feb; 129: S247-S269.

Pérez de León AA, Teel PD, et al. Integrated strategy for sustainable cattle fever tick eradication in USA is required to mitigate the impact of global change. Frontiers in Physiology. 2012; 3:195.

Pound JM, George DM, et al. Evidence for Role of White-Tailed Deer (Artiodactyla: Cervidae) in Epizootiology of Cattle Ticks and Southern Cattle Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Reinfestations Along the Texas/Mexico Border in South Texas: A Review and Update. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2010; 103(2): 211-218.

Schultz M. Theobald Smith. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008 Dec; 14(12): 1940-1942.

USDA-APHIS, Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program-Tick Control Barrier. Environmental Impact Statement. June 2013.

Really interesting article, and one I’ll be sure to pass on to my Parasitology class!

Very informative. I had no idea our beef supply in this country could be so at risk.