Tom Koerner/USFWS

The previous post, Cattle Fever Ticks Make a Comeback in Texas, looked at the growing problem of these two species of disease-carrying ticks in the United States more than a half century after their elimination from all but a narrow buffer zone along the Texas-Mexico border.

Significant changes have occurred in recent decades in Texas that have allowed the resurgence of these ticks, and the threat that they may reintroduce babesiosis (or cattle fever) to the US. This deadly animal disease is estimated to cost upwards of $1 billion every year if allowed to spread unimpeded in the US?

Texas, as with everywhere else in the world, is not the same place it was 100 years ago. That is when one of the most successful animal disease prevention programs in US history was well on its way to eliminating cattle fever ticks (Rhipicephalus annulatus and R. microplus) and the tick-borne diseases that they spread (caused by the protozoan pathogens Babesia bovis and B. bigemina).

A million cattle on average are imported into the US each year from Mexico, a large percentage through official border crossing points in Texas. Yet these animals are for the most part well taken care of, carefully inspected, and treated for ticks before coming in, meaning cattle fever ticks rarely if ever enter the US through this route.

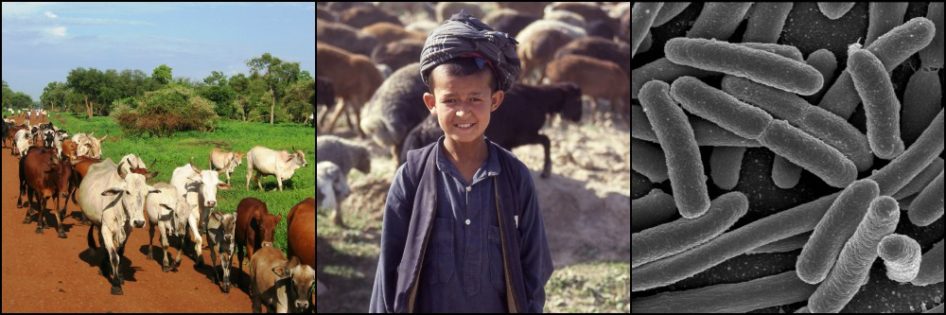

The problem lies elsewhere. Three broad changes have occurred pertinent to this story, fueled by people, their livestock, and wildlife. Each is intimately intertwined in a cause-and-effect relationship with the other two.

The Rise, Fall, and Rise of the White-Tailed Deer

As we saw in the previous post, the steady roll-back of cattle fever ticks (CFTs) in the US proceeded smoothly until reaching central Florida in the 1930s. It was discovered that dense populations of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) could sustain these ticks on pastures even when cattle had been removed from them for many months.

Why didn’t this same problem arise in other areas? Because in the early 20th century, white-tailed deer were nowhere near as common as they are today in the CFTs’ former range across the southern US.

White-tailed deer live from Canada’s Yukon Territory in the far north all the way to Peru and Bolivia in South America. They apparently thrived in the southern US for more than three centuries after Columbus landed in the Americas. But by the end of the 1800s, the white-tailed deer population in Texas was reported to be “almost extirpated”, with a few pockets of the species living in remote areas difficult for people to access.

The nilgai antelope, brought to the US from South Asia in the 1920s, is less abundant than white-tailed deer but also plays an important role in CFT tick ecology in Texas. Max Pixel

The dramatic decline was largely due to unrestricted hunting of the deer for skins, and meat for supply to the growing number of logging and mining camps in the region. And with the arrival of the same railroads that took cattle to Chicago for slaughter, these deer products also supplied population centers in the eastern US. The replacement of single-shot breech-loading rifles by the more rapid repeating rifles after the US Civil War (1861-65) made deer hunting that much more efficient, and these animals were soon all but gone.

Furthermore, the influx of European settlers to Texas, as to all the US, significantly altered habitats. The effects on white-tailed deer populations in particular are complicated, often ambiguous. For example, the Europeans’ introduction of cattle and especially sheep resulted in large-scale overgrazing in south Texas from the late 1860s through the end of that century. Combined with suppression of the natural cycle of wild fires there, vast grasslands transitioned into brush land.

This habitat is favored by white-tailed deer, which prefer browsing on shrubby plants over grazing on grasses. And brush provides them with more cover from predators. Yet the increasingly dense human population that provoked these positive environmental changes for the deer also led to more deer hunting, which outweighed the habitat advantages.

This white-tailed deer buck died (during the 2016 outbreak in the Florida Keys) from the same New World Screwworm that helped keep Texas deer populations at low levels in the first half of the 20th century. The screwworm fly was eliminated from Texas by 1966, with a few recurrences into the 1980s. Samantha Gibbs, US Fish & Wildlife Service

Added to human factors in the deer’s decline was the New World screwworm fly, which loves to place its eggs in the wet umbilical stumps of newborn fawns and, as we have seen recently in the Florida Keys, beside the head wounds of bucks fighting one another in preparation for the mating season. The larvae of these flies eat into the flesh all the way to the bone, leading to a painful death after a week or so.

Corrective Action

By the 1940s, as the cattle fever tick elimination program was winding down as a great success, trophy hunting of deer was becoming a popular sport. While access to vehicles and road construction, sparked by the developing oil industry, might otherwise have put an end to the deer population in Texas, game management helped avoid this.

In the 1950s, Texas imposed regulations that prohibited the killing of female deer, put a cap on the number of deer killed per hunter, and limited hunting of any deer to a specific hunting season, all designed to increase the deer population. Refuges were established and deer were brought in from other parts of the country and released to augment populations.

And by 1964, the New World Screwworm flies were eliminated from Texas, further reducing pressure on the deer.

These changes allowed the deer to take advantage of the now widespread brush land habitat in which they can thrive. From “almost extirpated” in the early 20th century, the white-tailed deer population in Texas had risen to close to 4 million by the early 21st century.

This heavy deer presence however means that pastures that are vacated of their livestock in order to starve and eliminate cattle fever ticks no longer stay empty when the cattle and sheep are gone. Deer are so abundant that they inevitably fill the void, providing the ticks with a blood meal and transport to new pastures. Sixty years ago the ticks would have starved to death and the livestock returned to a tick-free pasture.

The Rise of Exotic Wildlife

Complicating this scenario are exotic wildlife introduced for trophy hunting and now reaching high numbers in parts of south Texas.

While at least seven exotic species appear to be competent hosts for cattle fever ticks – axis, fallow, wapiti, and Eurasian red deer, aoudad sheep, and nilgai antelope – it is the latter that creates the most concern. Nilgai are large antelope native to the Indian subcontinent and have adapted well to south Texas brush and range land. Many wander freely along and on both sides of the Texas-Mexico border ,where the cattle fever tick buffer zone attempts to prevent them and other animals from wandering back and forth.

A Nilgai antelope painted in 11th century India. Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2001

From 13 nilgai introduced to Texas in the 1920s, today they are estimated to number around 38,000 there. The home range of individuals is much larger than that of white-tailed deer, with females observed to move up to 30 miles, most commonly in July and August when ticks are most active.

Nilgai also happily mix with cattle herds, facilitating infestation of the latter with the offspring of any cattle fever ticks the antelope may be carrying.

Tick Habitat

The same human alterations to the habitat that have been largely positive for white-tailed deer in south Texas have been doubly so for cattle fever ticks. These ticks crave high humidity and the larvae are very susceptible to drying out in the hot sun if they cannot soon find an animal host to feed on.

Dust storm in Texas, 1935. These storms from the Dust Bowl years of the Great Depression were testament to the significant environmental changes that followed the arrival of European settlers in the Americas. Not all of these changes were bad for the white-tailed deer population. NOAA George E. Marsh Album

The transition from grassland to scrub brush in large parts of south Texas offers more shade, and therefore longer life, to tick larvae awaiting a meal. Numerous species of invasive vegetation have also been implicated in increased tick larvae survival in the area.

Changing temperature and rainfall patterns accompanying global climate change are also believed to play an important role in providing improved tick habitat here, but that topic is for another post.

Tick Resistance

Last but far from least, the return of cattle fever ticks to the US is also partly attributable to the rapid evolution of ticks resistant to our best acaricides (tick-killing products) in recent decades. This has meant that the weekly to monthly treatments of livestock removed from CFT tick-infested pastures have not been killing all the ticks on those animals, making their elimination much more difficult.

Into the 1960s, tick control involved swimming cattle through dipping vats filled with an arsenic-containing acaricide liquid. The short tick protection time provided by this drug (1-2 days only), environmental contamination concerns and, eventually, development of resistance in ticks led to the switch to organophosphate-based acaricides in the 1960s, pyrethroids and amidines in the 1970s, and the macrocyclic lactones (including the avermectin and milbemycin drugs) in the 1980s.

Mexico conducted its own CFT-eradication campaign from 1974 to 1985. Within a few years, tick populations were found there that were no longer killed by normal doses of organophosphates.

When Mexico ended its CFT elimination efforts prematurely in the mid-1980s, resistant tick populations expanded. Ranchers there began using pyrethroid-based and amidine (Amitraz) acaricides when organophosphates were no longer doing the job in the 1980s, then macrocyclic lactones (such as ivermectin) when ticks developed resistance to pyrethroids in the mid-1990s. And tick resistance to both macrocyclic lactones and Amitraz began appearing in Mexico by the 2000s.

Today CFT ticks in northern Mexico have been found that are resistant to 2, in a few cases 3, different classes of acaricide. The options are shrinking fast.

I am not trying to pick on Mexico here. Only it is relevant to this story as the closest population of CFT ticks to south Texas. And highly favorable climatic conditions for CFTs (R. microplus in particular) in much of Mexico mean cattle owners are heavily dependent upon acaricide use. But acaricide resistance in CFTs is occurring all over the world, not just in Mexico.

Texas, of course, has not been immune to these rapid developments, which partly explains the problem with the cattle fever ticks’ return there today. Resistance to organophosphates began appearing in Texas ticks in 2005. Sonja Swiger, a veterinary entomologist at Texas A&M University, says cattle fever ticks in the state are now also resistant to normal doses of all pyrethroid-based acaricides.

I have jumped cursorily over the subject of acaricide resistance. It is indeed considerably more complex than I have alluded to here. There are different degrees of resistance, and the discovery of resistant ticks in a country or area doesn’t mean that all or even many ticks or their hosts are affected (yet!). Nonetheless, the prospects are not good.

I have overly generalized the cattle fever ticks, grouping Rhipicephalus microplus and R. annulatus together as one in this post for the sake of simplicity. But there are many differences. Habitats and thus range differ in Texas, as seen on this map of south Texas, and around the world. Problems with acaricide resistance are more evident in R. microplus. Giles JR, Townsend Peterson, et al.

Rethinking the Problem

This combination of increased numbers of wildlife, habitat changes favorable to cattle fever ticks, and tick resistance to acaricides are key factors in explaining the return of cattle fever ticks as a problem in the US after decades of good control.

The situation has forced a rethinking of strategies. Pasture vacation along with regular acaricide treatment of livestock continues. Treatment of white-tailed deer around the vacated pastures with ivermectin-laced corn and rubs that spread acaricide around the head and neck of the deer have been added to eliminate ticks on the deer.

Fencing along the Texas-Mexico border was abandoned earlier as maintenance was difficult. Numerous breaches occurred in the fence, allowing wildlife and livestock to cross. A few ranchers have placed high quality fencing around their pastures to prevent wildlife incursions while the pastures lay fallow to eliminate ticks. These have shown some success, but are very expensive and unlikely to offer a practical solution.

Scrubland in eastern Webb County, Texas, through which the Permanent Tick Quarantine Zone along the Mexican border passes.

By Billy Hathorn

Use of a CFT tick vaccine has been introduced in south Texas only recently. The vaccine produces antibodies in inoculated cattle that kill ticks when they take up the antibodies in a blood meal. While this can overcome many of the problems posed by acaricide resistance in the ticks, this too is very expensive. The protocol requires two initial vaccinations a month a part, followed by boosters every 6 months. Gathering up thousands of cattle on such expansive ranches can take days, lots of cowboys, and sometimes a helicopter.

There is still hope that the situation can return to the status quo ante, with ticks contained to occasional appearances in the buffer zone along the border with Mexico. But the options to achieve this are not great, and our best weapons in the past are not working like they used to.

Resources

Abbas RZ, Zaman MA, et al. Acaricide resistance in cattle ticks and approaches to its management: The state of play. Veterinary Parasitology, 2014 Jun; 203(1-2): 6-20.

Pound JM, George JE, et al. Evidence for role of white-tailed deer (Artiodactyla: Cervidae) in epizootiology of cattle ticks and southern cattle ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in reinfestations along the Texas/Mexico border in south Texas: a review and update. J Econ Entomol. 2010 apr; 103(2): 211-8.

Rodríguez-Vivas RI, Pérez-Cogollo LC, et al. Rhipicephalus(Boophilus) microplus resistant to acaricides and ivermectin in cattle farms of Mexico. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2014 Apr/Jun; 23(2).

Pérez de León AA, Teel PD, et al. Integrated Strategy for Sustainable Cattle Fever Tick Eradication in USA is Required to Mitigate the Impact of Global Change. Front Physiolo. 2012; 3: 195.

USDA-APHIS, Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program-Tick Control Barrier. Environmental Impact Statement. June 2013.