Rhesus macaque on Florida’s Silver River Anoldent

The ancestors of Florida’s rhesus macaques arrived in the late 1930s on the supposed whim of a local tour boat guide. What started as a handful of individuals is now believed to number in the hundreds, worrying public health officials that the macaques could transmit a deadly herpesvirus to human admirers imprudent enough to venture too close to the animals.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) are native to Asia and, along with several other macaque species, are commonly used as research subjects in medical laboratories. The man who released them on an island in Silver River, not far from the rolling horse country of Ocala, Florida, underestimated their willingness to swim. Their expanding population soon left the island and spread up and down the river, its tributaries, and beyond, possibly joined over the years by the occasional macaque escaped from a zoo or as a pet.

Periodic counts of the macaques reveal steady increases: a dozen in the 1940s, nearly 80 in 1968, up to 170 in 1981, though these censuses may have significantly underestimated the true numbers.

In the 1980s, Florida’s Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission became alarmed at the size of this invasive species’ population, both as a public health and public safety concern. Permits for trapping and removing macaques were issued beginning in 1984, and the captured animals were sold for use in medical research. Well over 1000 macaques are believed to have been removed in this way up to 2012, when the practice seems to have been halted in the face of public opposition.

Trapping likely had some impact on population growth, with estimates of 100-200 individuals today being similar to the 120 macaques estimated in 1993. There is concern that the recent end to trapping could lead to a big population increase.

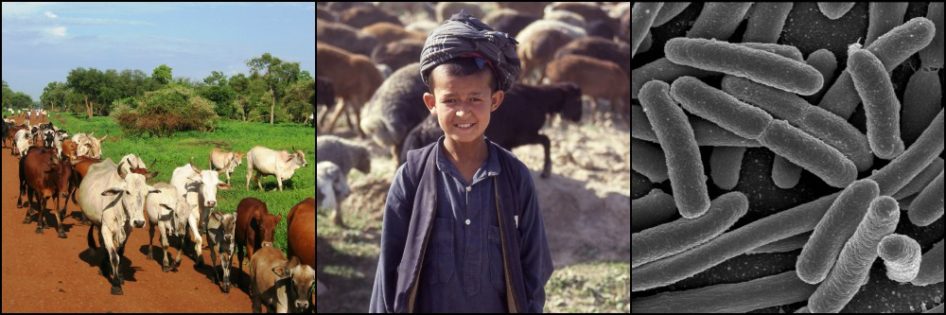

Macaques and Herpes Virus

The most concerning public health threat is a virus commonly carried by macaques called Macacine Herpesvirus (MHV, also commonly referred to as Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1, herpes B, and monkey B virus).

. In most rhesus macaque populations, whether free-living or in laboratories, anywhere from 70% to 90% of the adult monkeys harbor the virus. Testing of the Florida macaques in the early 1990s confirmed its presence there.

The saying “Herpes is for life” is just as true for MHV as it is for the human herpes simplex viruses commonly found in people. But the various herpes viruses in primates have many other similarities too. Generally the infection shows no outward signs of illness, the virus remaining dormant in a cluster of nerve cell bodies called the trigeminal ganglia tucked deep under the brain.

In times of high stress, however, an overtaxed immune system in the host allows the virus to become active. Virus travels along nerve axons to mucosal epithelial cells where they begin replicating, sometimes causing conjunctivitis (eye infections), vesicles (fluid-filled sores) in the mouth, and occasionally on the skin. Contact with virus shed in these and other body fluids (saliva, tears, urine…) during these stressful periods is required to infect other individuals. But in the majority of cases, even these stressed macaques betray no clinical signs of MHV infection.

Overcrowding, the presence of other illnesses, breeding season, laboratory testing…. all of these can cause a macaque to begin shedding the herpes virus. But it is estimated that no more than 2% of infected individuals are shedding MHV at any one time.

Oral lesions caused by herpesvirus in monkeys may look like this. UGA

Humans and Macaque Herpes Virus

Herpes viruses in general are known for being highly adapted to infecting a single or very narrow range of host species. Of the 35 identified herpes viruses of non-human primates, only two are known to be zoonotic. MHV is one of these. Yet only 50 cases of MHV have ever been documented in people, the first occurring in 1932.

All but one of these cases resulted from bites or scratches from medical laboratory macaques, accidental sticks with contaminated needles, or other contact with macaque tissues in the lab. A single case of person-to-person transmission occurred when a woman with a skin infection on her finger touched a vesicle on her husband’s skin where he had been bitten by a macaque.

A majority of cases occurred in the US, many in the 1950s and 1960s when rhesus macaques were favored for testing human polio vaccines. A resurgence occurred in the late 1980s with the use of these animals in HIV research.

As with many viruses adapted to a single species, the consequences are often devastating on the rare occasions the virus manages to infect a different species. Of the 50 human cases of MHV, 21 proved fatal.

Typically within a week of a bite from a rhesus macaque shedding MHV virus, the person develops a fever, head- and muscle aches, and sometimes vesicles at the wound site. After the virus moves from the wound along the nerves to the central nervous system, encephalomyelitis (brain and spinal cord inflammation) produces various neurological symptoms including hypersensitivity to touch, ataxia (decreased control over body movements), agitated disposition, and paralysis. The latter results in death from respiratory failure once the diaphragm is involved.

Certain antiviral medications significantly increase the chance of survival, but only if begun prior to the onset of neurological signs.

Breaking Down the Barriers to Transmission

Close contact greatly reduces barriers to disease transmission. This explains the worry over the growing macaque population along Silver River in Florida and the constant flow of tourists and boaters going there to see them.

The four or five distinct macaque groups living along the river favor swampy areas and are difficult to approach other than by boat. A 2013 study noted that while well over 80% of boats, including canoes and kayaks, slowed down or approached the river bank to get a better look at the macaques, only 12% of the 566 boats observed actually fed the monkeys. Of these, two boats moved close enough to allow the macaques to take food directly from passengers’ hands. The others simply tossed food onshore.

Despite concerns, the zoonotic risk of MHV outside of a laboratory is minimal. We know this from the long history of close human-rhesus macaque interactions over many centuries, particularly in Asia.

A study at a Hindu temple on the island of Bali, Indonesia showed that tourists and the large free-living macaque population around the temple commonly interact in such a way that MHV virus transmission is possible. Furthermore, 31 of 38 macaques from this same site tested positive for antibodies to MHV virus, a strong indication of infection. Yet, as far as we know, no humans have ever become infected with MHV from this, or any other, free-living macaque population anywhere in the world. It cannot be ruled out that cases have occurred and gone undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, but these certainly would have been very rare if they exist at all.

The amount of human contact with the Silver River, Florida macaques pales in comparison to interactions elsewhere. Various macaque species in Indonesia, India, or even Gibraltar (where Barbary macaques constitute Europe’s only free-living monkey population) depend on humans for up to 90% of their food. The Silver River rhesus macaques however depend on people for less than 5% of their food, meaning forced, potentially aggressive, interactions between people and monkeys emboldened by hunger may be less common than elsewhere.

Welcome Committee member in Gibraltar, doing his job. Nathan Harig (Picasa)

Public health officials are right to be wary of the potential threat of MHV in Florida’s macaque colonies. However the risk of zoonotic transmission is very low. Educating visitors on MHV virus and urging avoidance of direct contact with the macaques, particularly for immunocompromised persons, and seeking immediate medical care in the event of a bite or scratch from a macaque, would go a long way towards all but eliminating the risk.

References

Hogan B, Chandrasekar PH, et al. Herpes B. Medscape. 2015.

Huff JL and Barry PA. B-Virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) Infection in Humans and Macaques: Potential for Zoonotic Disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003; 9(2).

Riley EP, Wade, TW. Adapting to Florida’s riverine woodlands: the population status and feeding ecology of the Silver River rhesus macaques and their interface with humans. Primates. 2016; 57(2): 195-210.

Tischer BK, Osterrieder N. Herpesviruses—A zoonotic threat? Veterinary Microbiology. 2010; 140 (3-4): 266-270.