Storks on migration over Haifa, Israel. Several individuals of this species were found in this area carrying a particularly virulent form of West Nile Virus from Europe in 1998. David King

Migratory birds move hundreds to thousands of kilometers twice a year, often spanning continents. As they share certain diseases with people, it is not surprising that birds are frequently blamed for transporting these diseases around the world. But while birds are undoubtedly implicated in the geographic expansion of some emerging diseases, the more interesting question is why it doesn’t happen more often, given the hundreds of millions of birds on the move.

I have been fascinated with the miracle of bird migration ever since a series of visits to the Arabian Peninsula in the early 2000s. In the winter I saw birds similar to those nesting in the woods near my home in France just a few weeks before, and yet these same birds weren’t there when I returned to Arabia in the summer. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus may have first described this phenomenon over 24 centuries ago, realizing that these birds did not hibernate in winter, as some speculated, but undertook Herculean journeys to more auspicious climates in the south.

The Candidates

Birds are host to a handful of zoonotic diseases they can potentially transport with them during their peregrinations. These include, to name a few of the better known ones:

- West Nile virus (WNV)

- St. Louis encephalitis and Japanese encephalitis viruses, two other flaviviruses closely related to WNV

- Eastern, western, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses, which sometimes cause serious disease in horses and people

- Highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses

- Borrellia burgdorferi, the bacteria that cause Lyme disease

The Case of HPAI

Of most worry to public health authorities in much of the world is the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). Until a little over a decade ago, only low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) appears to have been carried by infected birds over long distances. These are then introduced into domestic birds, in which they can mutate into much more devastating highly pathogenic forms that wipe out whole chicken and turkey flocks.

There was little or no evidence that wild birds could carry HPAI. That changed in 2005, when thousands of migratory birds died from HPAI at a major migratory stopover point in west central China. It appeared that this new HPAI strain, called H5N1, could be carried by wild birds over long distances, then spread to other birds including domestic poultry on different continents. The rapid spread westwards supported this fear, with the virus arriving within a few months in the Middle East, Turkey, and Eastern Europe, and in 2006 showing up in sub-Saharan Africa and Western Europe. The new strain also proved capable of killing people, though so far such cases have been rare.

In the media frenzy of that period, I remember a popular discussion in one Middle Eastern country about trying to halt bird migration altogether – an, of course, impossible task. I heard similar talk in the US, where this H5N1 strain has never been found, with calls for the eradication of Canada geese.

Using radar to observe bird migration. The numerous green and light blue circles (echoes) in the Eastern US represent large numbers of birds taking off around sunset on another migratory night flight. You can view the streaming radar here. Click on the archived radar streams for March-April or Sept-Oct of any year, and pay special attention to the hours between dusk and dawn.

For a simple introduction to using radar to observe bird migration, see here.

West Nile Virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is another zoonotic pathogen in which birds likely play a role in intercontinental spread. Testing has confirmed that birds on migration can carry WNV infections, and outbreaks every few years in Europe may have been initiated by infected birds returning from Africa to Europe in the spring. This may still occur, but WNV is also enzootic (i.e. constantly present) now in parts of Europe and doesn’t require to be carried in from elsewhere for an outbreak to occur.

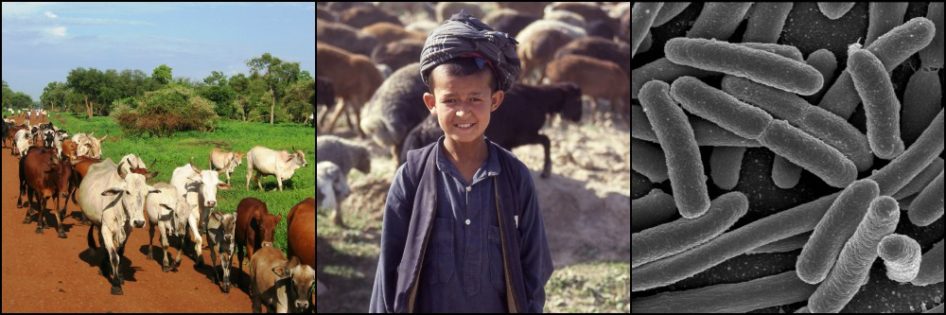

The strongest evidence of birds carrying WNV over long distances involves the movement of the virus from eastern Europe southwards to the Near East. In this case, 13 white storks at a migratory stopover point in Israel in 1998 were found to be severely ill from a particularly virulent form of WNV then circulating in southern Russia and Romania. The virus also sickened hundreds of people and killed several dozens.

This suggests that viruses may be equally transported by birds from temperate regions to the tropics, and not just the other way around.

This same virulent strain of WNV found in Israel in 1998 showed up a year later in New York City, the first case of WNV in the Americas. The virus spread steadily, reaching all 48 contiguous US states, Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean islands by 2004, northern South America in 2004, and Argentina in 2005. The pathogen has since been isolated many times from migratory birds, which almost certainly have played a role in its geographic expansion through the Western Hemisphere.

Map showing the spread of human encephalitis caused by West Nile Virus in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Did birds carry the virus from New York to Florida between 2000 and 2001? Or perhaps the annual human migration from the northeast US to Florida each fall was the cause, some of whom may have been infected, or transported infected mosquitoes in their cars? CDC

Stow-Aways

While the above diseases actually infect the birds that may carry them on migration, it is also possible for birds to transport diseases indirectly through the introduction of ticks (mosquitoes are less of a problem because they do not stay attached to birds long enough to be transported long distances). Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is an example.

Unknown in Turkey prior to 2002, the sudden appearance of this viral disease after that resulted in over 7,000 human cases in the decade through 2012. Hyalomma spp. and other suspected tick vectors were subsequently collected from several bird species in Turkey, leading to speculation that migratory birds may have introduced CCHF-infected ticks to the country.

Tick feeding on a songbird James Lindsey

To use the example of a strictly animal disease, the US Department of Agriculture invests a significant amount of money in preventing and monitoring for the introduction of ticks infected with the deadly cattle, sheep, and goat disease called heartwater, found on several Caribbean islands. The host ticks (Amblyomma spp.) feed on cattle egrets. This Old World bird species was first noticed in the Americas in 1937, after a group of them are believed to have been blown across the Atlantic Ocean to northern South America in a storm. They have made their way to North America and each new arrival from the Caribbean could in theory introduce heartwater-infected ticks.

Map showing the expansion of cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) populations in the Americas since their presumed arrival on a storm from Africa in 1937. Many cattle egrets in North America are migratory. Schoolbag.info

Other Explanations

Despite the convincing evidence that birds have played a role in the spread of some zoonotic diseases over long distances (in particular HPAI and WNV), there is also strong evidence that the role of these avian transporters is only a small, even miniscule, factor in these disease jumps and that other mechanisms of transport are much more important.

Surging global trade, intrastate movement of goods, the illegal wildlife trade, the explosion in airline travel, and ecological and climatic changes (that promote range expansion of mosquito and tick vectors or bird and mammal hosts) are just a few examples of pathways to disease movement that are probably much more significant than bird migration.

These two crested hawk-eagles from Thailand were confiscated at Brussels Airport in 2004. Neither showed overt signs of clinical disease, but both were carrying the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus, demonstrating another pathway for the transport of diseases over great distances. Paul Meuleneire

Even the often cited case of H5N1 avian influenza’s spread across Eurasia to Africa, which is not inconsistent with a bird migration hypothesis, can also be explained by the movement of domestic poultry and poultry products as part of regular trade.

In the devastating 2015 outbreak of H5N2 HPAI in the US, the general disease spread trend was from west to east and north to south, and occurred in the late winter to early spring months before bird migration would have reached many of these areas. Visits to multiple farms by delivery trucks and industry vehicles and equipment likely contributed more than wild birds to spreading the virus from infected to uninfected farms. 50 million poultry died in this outbreak. Charles Hoots

And in the frequently cited example of West Nile virus, the pathogen moved about as far west as it did south each year in its spread from New York City. Had migratory birds been the only, or even the primary culprit in WNV’s spread, the general trend should have been north to south and much less east to west. In addition, WNV appeared to move only about 70 km/month across North America. Had migratory birds been an important factor, WNV might have spread hundreds to thousands of kilometers during that time.

The H5N8 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus that jumped suddenly from Korea to Germany, the UK, and Italy in 2014 is not easily explained by migratory birds. I am aware of no bird species that undertakes anything close to such a journey. And the absence of disease anywhere in between these points militates against a relay-like transport of the virus between birds mixing from different regions, as depicted in the next figure below). Charles Hoots

The multiple factors potentially involved, of which migratory birds are only one, make it very difficult to identify the cause(s) of disease spread in any specific instance, and the role of migrating birds may be exaggerated in many cases.

Barriers to New Disease Introductions

Despite the theoretical suitability of birds as transporters of pathogens, the barriers to the introduction of a new disease in distant lands are numerous and formidable.

It is common to envision this process by way of a single infected mosquito, for example, exiting an aircraft or ship and biting a local person. That person becomes sick and is bitten by other mosquitoes, which bite other people, quickly multiplying until it is too late to stop it.

But diseases don’t tend to work that way. There is a minimum threshold for success in most cases, a specific number of pathogenic organisms that must be present in order for them to take hold and establish themselves. It is much like the earliest European settlements in the Americas, some disappearing without a trace until larger numbers arrived and a few failures here and there could not halt the whole process.

Because of this, a single infected bird, or even several, will likely not be enough to successfully introduce a disease to a new place. The case of West Nile Virus in the US admittedly presents a mystery in this respect, as the most common explanation for its introduction is the arrival of perhaps a single infected mosquito or captive bird into New York City on an aircraft.

A depiction of the hypothetical relay spread of pathogens between migrating birds.

On their northern breeding grounds in Siberia and Alaska, birds may come into contact with other birds that spend the winter far to the west or east of them, allowing diseases to spread between them. For example, some birds wintering in Korea may breed in eastern Siberia or Alaska, where they come into contact with birds that overwinter in North or even South America (represented by blue line in the map). Despite this link, use of this route by pathogens is surprisingly rarely exploited with success. Wikimedia

Furthermore, infected birds are often so sick that they cannot undertake their migratory journey. This is true for H5N1 avian influenza, at least in the later stages of the disease. It has also been true to some extent for virulent forms of WNV.

Even if individual infected birds are well enough to migrate, the viruses in question remain infectious for only a short time in the bird host, often for only 2-4 days. With the exception of a few songbirds that make non-stop flights from breeding to wintering grounds, most migrators fly for only part of the day (either at night for many songbirds or during the day for raptors), feeding and resting during the other part of the day. With an infectious period of just a few days, most migrating birds would not be able to spread the disease very far at one time.

If the newly introduced pathogen is closely related to an already circulating pathogen, there may be some cross-protection. Healthy people and animals would be able to fight off infection without becoming ill and the disease may thereby fail to establish itself.

Most importantly, establishment of a new disease assumes all the requirements of that disease are met. Except for avian influenza, most pathogens have high demands, such as the presence of competent mosquito or tick vectors. Without these, introduced pathogens disappear without a trace.

Focus on What is Most Important

In general, the evidence presented for the introduction of new diseases over long distances by bird transport is often (though not always) less than convincing. West Nile virus and the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus offer the best evidence of emerging, zoonotic diseases spread over long distances by migratory birds. But even in these examples, other factors likely play more important roles than wild birds. While we should not ignore the latter, we are well advised not to lose sight of the other pathways to intercontinental disease spread, factors over which we have much more control than the migration of hundreds of millions of wild birds that show no regard for national borders.

References

Hamer SA, Goldberg TL, et al. Wild Birds and Urban Ecology of Ticks and Tick-borne Pathogens, Chicago, Illinois, USA, 2005–2010. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2012 Oct; 18(10).

Pradier S, Lecollinet S, and Leblond A. West Nile virus epidemiology and factors triggering change in its distribution in Europe. Rev. sci. tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 2012; 31(3): 829-844.

Rappole JH and Hubálek Z. Migratory birds and West Nile virus. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2003; 94:47S-58S.

Saito T, Tanikawa T, et al. Intracontinental and intercontinental dissemination of Asian H5 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (clade 2.3.4.4) in the winter of 2014-2015. Rev Med Virol. 2015 Nov; 25(6):388-405.

Sounds logical and rational. I agree with write up that the thresh hold or the equilibrium of the natural defense forces i.e. interaction of agent/host/environment has to be disturbed before the onset of large no. of cases to be reported, which later take the shape of epidemic.

Nice write up…….only wishing our Veterinary services are up against this in Africa

It is not an easy task, Dr. Anebonam. Even for countries with abundant resources.