Human cases of H7N9 avian influenza virus FAO

A new avian influenza virus now rivals H5N1 as a candidate for the potential cause of a human pandemic one day. H7N9 first appeared in people three years ago and shares many characteristics with H5N1. But some key differences make this newer virus more difficult to keep tabs on as it circulates quietly through poultry flocks.

H7N9 caught the public health field’s eye in March 2013, when the first human cases of the virus were diagnosed in China. Fever, severe respiratory symptoms, and often death were the result, particularly in older persons already weakened by other health problems such as diabetes, heart failure, or obesity. Spikes in the number of cases have occurred every winter since then, between December and May.

Through March of this year 750 human cases of H7N9 have been confirmed, with at least 295 deaths attributed to the virus. In the three years since its appearance, infections have concentrated on Guangdong and Zhejiang provinces, in southeastern and eastern China, respectively. Only three cases have occurred outside China: two in Canada and one in Malaysia, all in people who had recently visited China.

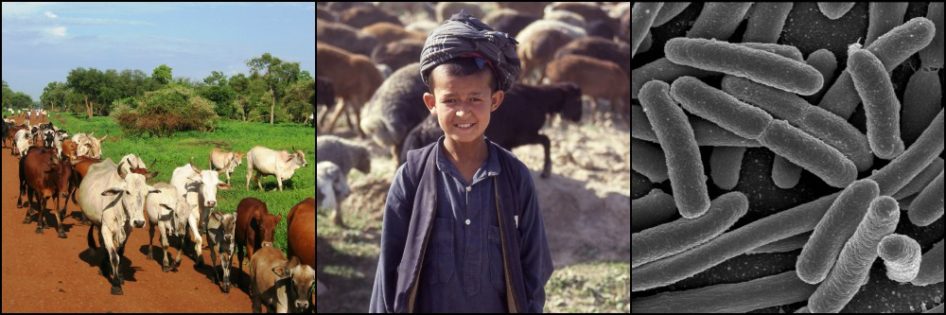

The common denominator in the growing number of cases is contact with poultry, in particular at live bird markets which thrive in much of China. Yet no poultry are dying from this virus, as would have been expected. Something is different.

Similarities

As discussed in an earlier post on highly pathogenic avian influenza, H5N1 is the first avian influenza (AI) virus to make many people really sick. In fact, it kills over half of those infected with it. H7N9 has now succeeded in doing the same, able to occasionally bind receptors in certain alveolar and bronchial cells of the human respiratory tract and infect them.

The new virus kills about 1/3 of those it makes ill. That’s about half the case mortality rate of H5N1. However H7N9 has caused as many human cases in three years as H5N1 has caused in the 19 years since first emerging as a human pathogen in 1997.

Despite the more rapid spread, all but a handful of cases have come from direct contact with poultry or poultry premises. As with H5N1, person-to-person transmission is fortunately poor to non-existent – so far….

But this could always change. H7N9 is no different from other AI viruses in its propensity to mutate and reassort (exchange segments of genes with other influenza viruses simultaneously infecting the same cell). Research has shown that the current H7N9 virus is made up of genes contributed from three different AI viruses:

- the H7 (hemagglutinin protein) gene is from a virus commonly found in ducks and geese;

- the N9 (neuraminidase protein) gene is from another virus of wild birds;

- other of the virus’s 11 genes are from an H9N2 virus common in chickens.

Proposed reassortments leading to H7N9 virus FAO

The fear is that further genomic changes along these lines could lead to improved adaptation of the virus in binding human cells and/or in spreading between people, rather than only from poultry to people.

Differences

Other than its moderately better ability to infect people and the fact that it has been limited for the most part to China, the H7N9 virus differs in one very significant way from H5N1. The latter is classified as a highly pathogenic AI virus because its entry into poultry flocks leads to massive die-offs that kill up to 100% of birds in some cases.

Though tragic for the birds and their owners, the advantage is that H5N1 virus is easily recognizable in these flocks and control measures can immediately be undertaken to prevent its spread to other flocks and to humans (this usually means culling of any surviving birds in the flock and close surveillance of nearby or exposed poultry flocks, among other measures). Only highly pathogenic AI and Newcastle disease virus are capable of causing such damage in poultry, so the diagnosis is not difficult.

The finding that H7N9 infects poultry without causing any clinical signs in them is disturbing. Stopping the virus from spreading in poultry is the only way to stop it from being passed on to humans. If we can’t recognize it in poultry without testing flocks randomly for subclinical infections, that puts a huge burden on the surveillance and monitoring system. Otherwise we will be alerted to the virus only by the confirmation of human cases. All flocks that an infected person may have come into contact with must be tested, by which time the virus may have spread to other flocks.

And with live bird markets playing an important role in transmission, the difficulties are multiplied several fold. Poultry from different farms mix and exchange viruses at these markets, then are sent to new farms or returned unsold to their own farm, but now with viruses picked up from other birds. Identifying and testing infected flocks would be a nightmare when the only trail left by the virus is a few sporadic infections in people.

The current winter spike of H7N9 infections has produced fewer cases (75 through March 2016) than in previous winters (270 cases from Dec 2013 – May 2014 and around 200 from Nov 2014 – March 2015). This has reassured health officials that efforts such as closures and greater regulation of live bird markets in China are bearing fruit. But that could change at any moment given avian influenza virus’s ability to rapidly alter its genome.

References

- Avian Flu Diary. Retrieved from http://afludiary.blogspot.com/

- CDC. Avian Influenza A (H7N9) Virus. Influenza A 2014.

- FAO. H7N9 Virology. Animal Production & Health 2015.

- Tanner WD, Toth DJA, Gundlapalli AV. The pandemic potential of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus: a review. Epidemiol. Infect 2015; 143: 3359-3374.

- Wu D, Shumei Z, et al. Poultry farms as a source of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus reassortment and human infection. Scientific Reports 2015; 5.

What about ingesting infected poultry? Does that carry any risk? Or does the high temperature used for cooking kill the virus?

Hi, Lina. I don’t think there are any known cases of H7N9 being contracted through cooking and eating poultry meat or eggs. All but a handful of cases seem to originate from contact with live bird markets and poultry slaughter facilities.

In any event, cooking poultry meat and eggs to 70°C would kill the virus (must be cooked all the way through). In theory, the bigger risk would be to those preparing the poultry meat or eggs. Strict hygiene to prevent contamination of prepared foods with uncooked poultry or eggs is important – and not just in preventing avian influenza viruses, but also a number of other zoonotic viruses and bacteria.