New World screwworm maggots on an endangered Key deer. The injuries on rutting males are particularly vulnerable to the fly. Early infestations can be treated effectively in pets, livestock, and people. But identifying and treating infested wildlife is difficult. Charles Hoots

When the presence of New World Screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) was confirmed in the Florida Keys in September 2016, it was the first non-isolated appearance of the parasite in the United States in over 30 years. While the devastation to endangered wildlife on this archipelago has been significant, if the fly spreads unchecked to the mainland it could result in losses approaching $1 billion annually.

The release of large numbers of sterile male flies is the only known method to eliminate established New World Screwworm (NWS) populations. Identifying the geographical extent of the invaders is the critical first step. The flies typically are not great wanderers and refuse to cross open water. But when those in Florida began turning up on nearby islands with no land links to neighboring islands, the sterile fly release campaign became that much more complicated.

The Culprits

The NWS flies are metallic blue-green in color and superficially resemble many other species of blow fly (family Calliphoridae) that swarm on exposed flesh in and around wooded areas. While other blow flies search out the flesh of dead animals on which to oviposit (lay) their eggs, the NWS fly is unique in that it requires the flesh of a live animal to feed the larvae, or maggots, that hatch from its eggs.

Attracted by the smell from the wound of any warm-blooded animal (including people), a female NWS fly oviposits an average of 300 eggs at a time on the periphery of a wound site as small as a tick bite. The eggs hatch within a day and the larvae enter the wound to eat their way down sometimes to the bone. After a week or so, the 17mm (¾-inch) long larvae exit the wound and drop to the ground. Fleeing sunlight, they burrow into the soil and secrete a protective covering, or puparium, within which they mature into an adult fly. FAO

The Victims

The NWS outbreak was first discovered in ailing Key deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium), a subspecies of the larger white-tailed deer of the mainland US. Rutting season occurred simultaneously with the NWS’s arrival, and the flies have taken advantage of the antler wounds resulting from the competing bucks. Of the 120 or so known deer that have died or been euthanized due to severe infestation, only a dozen or so have been females. Gaping holes as big as a grapefruit and filled with squirming maggots (see top image) have spurred public support for the government’s effort to eliminate the fly.

been females. Gaping holes as big as a grapefruit and filled with squirming maggots (see top image) have spurred public support for the government’s effort to eliminate the fly.

Down to as few as 25 individuals in the early 1950s, the Key deer population was listed as federally endangered in 1967. With an estimated 1000 or so Key deer at the beginning of the NWS outbreak, the carrying capacity of the federal refuge established to protect the deer is believed by biologists to be around 750 individuals.

Before its elimination from the eastern US in 1959, NWS killed anywhere from 20-80% of the annual white-tailed deer crop there, laying their eggs around the wet umbilical stumps of fawns. It is hoped, and likely, that the current effort to eliminate the flies will progress quickly enough to spare the newborn fawns in April-May, the main fawning period in the Keys.

A Key deer buck (Odocoileus virginianus clavium). The endangered Key deer descend from mainland white-tailed deer isolated on the archipelago when rising sea levels submerged the area around 15,000 years ago. The subspecies is smaller in size, more saltwater tolerant, and reproduces more slowly than white-tailed deer. Averette

The Threat of Escape

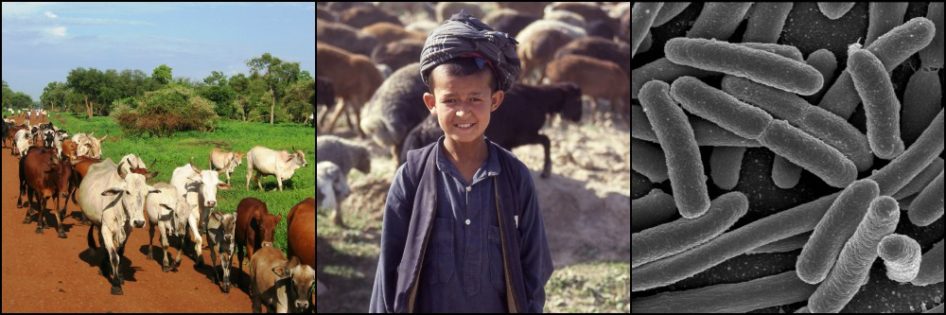

Fortunately, the Florida Keys have virtually no livestock other than 15-20 horses and a handful of pet goats and pigs. Were the NWS fly to spread from these islands to the mainland, the livestock industry could be turned on its head.

Before NWS’s elimination from the US, cattle, sheep, and goat owners had to time births, brandings, castrations, sheerings – anything that could expose an animal’s flesh – with cooler periods when fly activity was lowest. Even then, cowboys rode the pastures inspecting individual animals every few days for wounds and treating them with insecticide when found. NWS infestation was considered by many to be the most important impediment to livestock production in the US.

When NWS was progressively eliminated from the US in the late 1950s and 1960s, the cowboy profession all but dried up. Today cow-calf herds may go weeks without getting close to a human being. Unopposed reappearance of the fly in livestock areas is estimated to result in losses of several hundred million dollars annually from deaths and lost production of infested animals and the constant monitoring and treatment of herds.

A typical scene of various blow fly species that quickly collect on a carcass. While similar in size and metallic tint and color to the New World Screwworm blow fly, the latter would not lay eggs on a dead animal, though the female fly in particular may visit for a meal. Blow flies are commonly used in forensics to determine time of death of a corpse. Laszlo Ilyes

The Arsenal: Sterile Fly Release

Fortunately, we have a very effective tool for eliminating the NWS. E.F. Knipling recognized in the 1930s that female NWS flies mate only once in their 10-30 day lifetime, while males can mate repeatedly. He speculated that overwhelming the wild fly population with sterile male flies would soon ensure that all female flies only mate with sterile males. The eggs oviposited on wound edges would fail to hatch and the population would disappear.

Brief exposure of NWS pupae to high energy electromagnetic radiation in the laboratory within 2-3 days of adult fly emergence was found to render close to 100% of male NWS flies sterile, and without significantly changing their behavior.

After a more or less successful test run on Sanibel Island, Florida, the so-called Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) was used on the Caribbean island of Curaçao in 1954-55. Every week each of the island’s 440 km2 received 2600 sterile flies dropped by aircraft. Both male and females are released because it is too expensive to separate them.

After three weeks, some 70% of NWS eggs found on wounds were sterile. After 6 weeks, this percentage rose to 84%. After 9 weeks, few eggs could be found at all on the island, and ALL were sterile.

One of the three larval stages of the New World screwworm. The two black bony hooks are used to rasp flesh away for consuming. The tapered body segments resemble a screw, whence the common name of the species. John Kucharski

SIT worked, and it has worked time after time in all but one instance ever since. US livestock owners raised money to start their own campaign after the success on Curaçao. Between 1957-59, NWS was pushed back from Florida to the Mississippi River, and by 1966 enzootic NWS was gone from all of the US.

Mexico followed, not without some hiccups (see below), eliminating the flies by the early 1990s. The rest of Central America, from north to south, was steadily freed of the fly by 2006, when Panama was officially declared NWS-free.

Progression of New World Screwworm elimination using the Sterile Insect Technique. Northern and central South America have vast NWS-infested areas and have not undertaken elimination programs. The fly remains common there. In the Caribbean, only Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Trinidad/Tobago, and Cuba have not eliminated the fly. Adapted from OIE map.

Today the US government funds the majority of a sterile fly research and production facility outside Panama City, Panama. Sterile flies are regularly released around 30,000 km2 of inaccessible swamps on the Panama-Colombia border. The area forms a barrier to NWS incursions from South America and, while expensive to maintain, is considerably less expensive than dealing with the regular reappearance of the flies in Central and potentially North America in the absence of the barrier. This plant in Panama is supplying the sterile flies released in the Florida Keys today.

Surprises

Despite the buffer zone in Panama, there are still breaches. We do not yet know where the NWS flies affecting the Florida Keys came from. But genetic testing is underway to compare with NWS populations in South America and the Caribbean. These may tell us their origin or, at least, where they did not come from. Either would improve our understanding of the fly and help better control it in the future.

Many Floridians speculate that the flies were introduced from Cuba, the closest country with enzootic NWS flies and only 150 km from the Florida Keys. But the fly could just as easily have arrived on a plane from any other enzootic country, probably on a pet.

One thing is relatively certain: NWS did not fly on its own from Cuba, or anywhere else, to Florida. The flies do not like to cross even small stretches of open water. The flies rarely move more than a few kilometers so long as sufficient hosts (i.e. animals with wounds) and fresh water are available. Until 1933, the Mississippi River formed an effective barrier to NWS. When severe drought in the west led to large movements of livestock to the southeast, NWS came with them for the first time.

An adult female New World Screwworm fly with batch of eggs oviposited in typical neat rows described as like the shingles on a roof. These will hatch and the larvae burrow into the wound to feed for 5-7 days. Note the blue-green metallic color of the adult fly and 3 dorsal thoracic bands that separate this blow fly species from all other common blow flies except the closely related Cochliomyia macellaria. Nash

The NWS flies recently discovered in Florida were initially limited to Big Pine Key and neighboring No Name Key, where the majority of the Key deer population is located. But within a couple of weeks, the US Department of Agriculture’s NWS expert entomologist John Welch, along with a team of experts from the sterile fly facility in Panama, detected flies on nearby islands too.

Speculating that they may have been transported as undetected hitchhikers in vehicles, the team looked for wild flies on an island some 2 km from the nearest land and inaccessible except by boat. Their effort revealed flies on this island as well. Cars were not the culprit.

Welch says he has never seen NWS flies cross such a long stretch of water. He speculates that an infested deer could have swum to the island, as they are known to do, colonizing it with the flies. But “I’ve learned to never say never, and this is another reason why,” Welch says.

While curious, this information is not likely to compromise the success of the elimination campaign in Florida. NWS is more likely to be spread by an infested pet dog or cat slipping undetected through the animal checkpoint established by the Florida and US Departments of Agriculture on the road leading off the archipelago.

A Panamanian expert stares at the flies on rotting liver, used to attract female NWS flies as part of surveillance efforts. Only one other common blow fly in this region, Cochliomyia macellaria, has the three dark longitudinal stripes on the upper thorax present on the NWS fly. Differentiation of the two species by differences in the color of the wing base, the lower abdomen, and the female’s neck are difficult to detect and surveyors rely more on behavioral differences. C. macellaria, whose larvae often feed on the dead tissue left behind by burrowing NWS larvae, are nervous, moving constantly over the rotting liver, disturbed by the slightest movement, their bodies raised as if on stilts. The NWS females, when present, take longer to arrive on the liver but swoop in with a loud buzzing. Once on the liver, they lap up the juices to nourish their developing eggs, and move but little, resting low on their legs. Male flies often watch from a nearby plant, waiting for a female to mate with. The males feed rarely, if at all, in their brief adult lives. Natalie Wendling

Yet the fly’s willingness to cross water reinforces the fact that, in order to be efficient, sterile fly release must be accompanied by good epidemiological information, surveillance of flies and animals in infested and neighboring areas, treatment (or culling, in advanced cases) of infested animals to limit new flies, strict monitoring of animals moving out of infested areas, and communication with the public to ensure their support.

If All Goes Well…

Jamaica is the only concerted sterile fly release program (1998-2009) that has not met with success, and this was apparently due more to complicating political, economic, and social factors than to technical problems with the SIT technique.

Unexpected problems can creep up however.

When NWS was driven out of the US, a buffer zone with regular sterile fly releases was established on the 2400-km-long Mexican border. The area proved too vast and regular incursions of the fly occurred in Texas until 1982, when it was decided to move the barrier south to the Tehuantepec Isthmus (see map above), where only 220 km separate the Pacific Ocean from the Gulf of Mexico. Such great expanses of infested territory do not present a problem in the Florida Keys, with its tiny, isolated islands.

Occasional quality control issues arise too. In the early 1970s, it was discovered that sterile male flies grown at a facility in southern Mexico would mate only in the afternoon and were poor flyers, compromising their ability to compete with fertile male flies. The problem was quickly corrected.

Quality control: Each release chamber contains one petri dish with about 100 pupae in it. Two days after each release, the petri dish contents are examined for percentage of pupae with flies that did not emerge (less than 10% is considered acceptable) and ratio of male to female flies. Successive generations of sterile flies can suffer losses in vigor and condition, i.e. competitiveness with wild, fertile male flies. Careful monitoring is necessary in order to catch these changes early. Natalie Wendling

Sterile flies are often dropped by low-flying aircraft. The islands of the Florida Keys are too small however, and winds too variable to make this a viable option. Too many of the released flies would end up in the water and drown. Instead, sterile pupae with their enclosed flies on the verge of emerging are set out at various wooded sites in and around infested areas, from which they disperse to cover infested areas.

Limited by the availability of hosts with open wounds, a population of 100 NWS flies/km2 is considered a heavy infestation. On Big Pine Key alone, with an area of about 30 km2, over 2.1 million sterile flies are being released each week. That means 70,000 released flies per km2, compared to a conservative estimate of 100 wild flies per km2, giving a ratio of 700 sterile flies to 1 wild fly. Other SIT programs have proven successful with less than a 100 : 1 ratio, so this should be more than sufficient to eliminate the flies from the Florida Keys, barring any unforeseen problems.

Sterile fly release chamber. There are two chambers per site and each chamber contains four trays filled with a total of about 76,000 pupae, each containing a fly on the point of emerging. The plastic cover is to protect from rain. Emerged flies can just be seen on the white Styrofoam cover. Charles Hoots

The sterile fly releases are scheduled to continue for at least six months, then 4-6 weeks beyond when the last known infested animal is found. Consistency is critical. It has been estimated that each week missed for releasing the flies once the campaign has begun results in up to 2 extra months of releases necessary to eliminate the flies. With the end of the hurricane season, such disruptions in the releases are unlikely. Cooler weather and an end to the rutting season in the Key deer further favor the fly elimination effort.

None of the potential problems mentioned above is insurmountable, though surprises beyond the newly discovered island-hopping abilities of these flies are always possible. While the campaign is expensive, with millions of fly pupae flown in twice a week from Panama (it is too expensive and long to establish a sterile fly facility in the US in time to address this outbreak), the costs of the fly spreading beyond the Keys would be much greater.

References

Alexander JL. Screwworms – Zoonosis Update. JAVMA. 2006 Feb; 228(3): 357-367. Available here.

Catts EP and Mullen GR (2002). Myiasis (Muscoidea, Oestroidea). In Mullen G and L Durden (Eds.), Medical and Veterinary Entomolgy (317-348). Elsevier. Available here.

Mastrangelo T and Welch JB. An Overview of the Components of AW-IPM Campaigns against the New World Screwworm. Insects. 2012 Oct; 3: 930-955. Available here.

Reichard R. Case studies of emergency management of screwworm. Rev. sci. tech. Off. Int. Epiz. 1999; 18(1): 145-163. Available here.

Tokarz LR. A Short History of the Screwworm Program. 2016 Jul. USDA APHIS. Available here.