Goats at water hole, South Sudan Charles Hoots

Rift Valley Fever outbreaks have long been predicted in Uganda. But when the nation declared its first ever outbreak of this zoonotic virus last week, it could hardly have occurred in a more unlikely part of the country. This is just the latest in several surprises this mosquito-borne virus has thrown at us over the past few decades.

Five Ugandans in the far southwestern district of Kabale, along the border with Rwanda, have been confirmed with Rift Valley Fever (RVF) virus, one of whom appears to have died from the infection. While this may not be a high number, an outbreak of disease in humans (epidemic) is defined simply as “a higher than expected incidence of a particular disease in a given area.” So five cases constitute an outbreak when normally no one is ill from the disease.

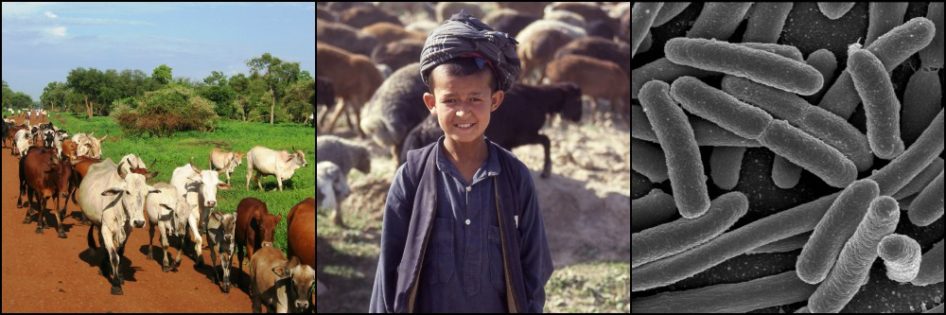

Under the right conditions, RVF virus is spread by certain mosquito species between cattle, sheep, goats, camels, people, and possibly wildlife. Infection is often noticed in livestock when large numbers of abortions occur in herds. Sheep are most severely affected, with up to 90% of infected lambs dying and up to 30% of adult sheep. Soon after these livestock abortion storms offer the first clues of an RVF outbreak, people begin coming to hospitals complaining of fever, headaches, and muscle aches (abortions do not typically occur in pregnant women with RVF). These people have commonly caught the disease while handling aborted fetuses, butchering infected animals, or otherwise coming into contact with body fluids of their sick livestock. Mosquitoes play a role too, but probably only secondary in transmission to people.

It seems that only a small portion of RVF infections in humans cause actual illness, and an estimated 1% suffer serious enough signs to actually seek medical care. The situation is complicated by the fact that most RVF outbreaks occur in rural areas where medical care is not always an option, even without the added obstacle of heavy flooding. A very small number of cases can cause either temporary blurred vision, encephalitis (brain swelling), or, as with the patient who died recently in Uganda, hemorrhagic disease (internal bleeding). The latter kills about 50% of those who come down with this form of the disease.

RVF virus is endemic in Uganda’s East African neighbors, as well as southern Africa and parts of West Africa. The virus lies low in these places, sometimes for decades, awaiting the ideal conditions presented by unusually heavy rains. In fact, a large majority of RVF outbreaks have followed closely on the heels of El Niño events. Even in Uganda, where no illness due to RVF has been diagnosed before, previous testing has shown 10% or more of people and cattle in parts of the country harbor antibodies to RVF virus. This means their immune systems have at some time in the past been exposed to the virus, though probably rarely in quantities or circumstances sufficient to cause illness.

The Peculiar Case of Kabale,Uganda

With an El Niño event causing floods in much of East Africa over the past few months, RVF outbreaks have been predicted there, including parts of Uganda. But Kabale, Uganda was not one of them!

Outbreaks of the disease in East Africa tend to favor semi-arid, sparsely wooded grasslands, a far cry from Kabale’s cool, tropical, green mountains. The lush Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, the world’s premier mountain gorilla tourism spot, is located nearby.

Even more importantly, unlike most of the rest of Uganda, Kabale district has actually had significantly less rainfall than normal over the past 7 months.

Deviation of rainfall in Nov 2015-Dec 2016 from average rainfall during this time period in previous years in Africa. Note the current above-average rainfall in all of Uganda (circled area) except the SW region, where Kabale is located. USDA

In general, RVF-infected mosquitoes of the Aedes genus pass on the virus in their eggs, which their mothers carefully place well above the water line near shallow water bodies. These eggs must be submerged before they can hatch, and can wait patiently for many years for another flood heavy enough to achieve this. When it finally comes, billions of Aedes mosquitoes, some infected with RVF, mature into adults. The females then spread the virus to local livestock, their favorite menu item (the males don’t feed on blood). The rich new vegetation that sprouts along with the heavy rains provides the mosquitoes with much needed protection from the sun.

Several weeks later, when stagnant pools of water are all that remain of the floods, conditions are propitious for other species of mosquito eggs to hatch (Culex spp. among others). These mosquitoes are less picky and feed on both livestock and people. This explains why livestock typically are the first sentinels of an RVF outbreak, followed by human cases later as the Culex mosquitoes get into the action.

Rift Valley Fever life cycle CDC

But Kabale has shown a different pattern.

Kabale has relatively low livestock densities compared to many other areas of Uganda. Under typical circumstances, when flooding releases the waves of RVF-infected Aedes mosquitoes, the more livestock for them to feed on, the more efficiently they spread, or amplify, the virus. If the outbreak then spreads to an area with low livestock densities, RVF in humans may increase as mosquitoes have less livestock to feed on and so feed on people instead. But to get going in the first place, RVF should prefer areas with lots of livestock, not less, and that is not the case in Kabale.

In fact, the outbreak in Kabale does not even appear to be affecting livestock much. Preliminary testing of 67 goats in Kabale has found evidence of previous RVF exposure (whether recent or long ago) in only a single animal, or 1.5% of those tested. This is less than might have been expected even in the absence of an RVF outbreak. So the appearance of RVF in Kabale remains a mystery for now.

There have been other mysteries in the past. The first RVF outbreak outside of sub-Saharan Africa occurred in 1977, in Egypt, followed by outbreaks in Madagascar in 1991, and, in 2000, across the Red Sea on the coastal plain of Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Each time, it appeared RVF would soon spread further abroad. Even in southern Europe and the United States, both of which have suitable climates and are home to numerous mosquito species shown to be capable of carrying the virus, preparations are in place to deal with the arrival of RVF. Yet, other than Indian Ocean islands nearby to Madagascar, little further spread has occurred so far.

Satellite monitoring evaluates rainfall and deviations from the normal vegetation growth in Africa, providing an early warning system for RVF hotspots since the 1980s. Yet the Kabale RVF outbreak shows us that weather patterns are just one, albeit critical, part of the story. And it reminds us of the many things we don’t know about this virus.

References

Himeidan, YE, Kweka, EJ, et al. (2014). Recent outbreaks of Rift Valley fever in East Africa and the Middle East. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 1-11.

Linthicum, KJ, Britch, SC, and Anyamba, A. (2016). Rift Valley Fever: An Emerging Mosquito-Borne Disease. Annual Review of Entomology, 61, 395-415.

Mansfield, KL, Banyard, AC, et al. (2015). Rift Valley fever virus_A review of diagnosis and vaccination, and implications for emergence in Europe. Vaccine, 33, 5520-5531.

Pittiglio, C, Pinto, J, et al. (2015). El Niño and increased risk of Rift Valley fever to countries. Empres Watch, 34, 1-8.

How does El Nino and La Nina impact RVF?

Hi, Stephanie. Anything that affects populations of Rift Valley Fever mosquito vectors will presumably influence outbreaks of the disease. With mosquito populations linked, among other things, to rainfall, the impacts of El Nino and La Nina events tend to be due to changes in normal rainfall periods and amounts. Very generally, I believe El Nino tends to result in higher rainfall than average in East Africa and less rainfall than average in southern Africa. La Nina tends to have the reverse effect. So more RVF outbreaks may be predicted during El Nino events in east Africa and more in southern Africa during La Nina events.

Of course it’s rarely that simple. The heavy rains of this year’s El Nino event have so far resulted in a single reported RVF outbreak in east Africa (in SW Uganda). And, as noted in this post, the affected area in fact had lower than normal rainfall this year! Never a dull moment.

Hi Charlie,

Have you heard any updates after the recurrence of RVF in Uganda in June? And where did you find out the results of the livestock testing? I haven’t been able to find that in my online searches.

Many thanks!

Hi, Jeanne.

Since this blog post in March, I believe Uganda had a single declared case of human RVF, in June 2016. That’s the only one I know of. I will send you some information on the animal testing directly.

Thank you for reading the blog,

Charlie