Livestock interventions can offer an effective means of improving livelihoods, food security and women’s and youth empowerment in low-income countries. However, mistaken comparisons to the negative impacts of intensive livestock production in wealthier countries have reduced the popularity of livestock activities among some aid organizations and donors. When projects do address livestock, it is sometimes only an afterthought — a small part of a larger project, planned using a template of popular go-to activities which are not always appropriate for the situation.

This article describes a few of the more common misconceptions surrounding livestock in development and humanitarian work and encourages planners and implementers to take them into account when considering their own interventions.

Livestock and the environment

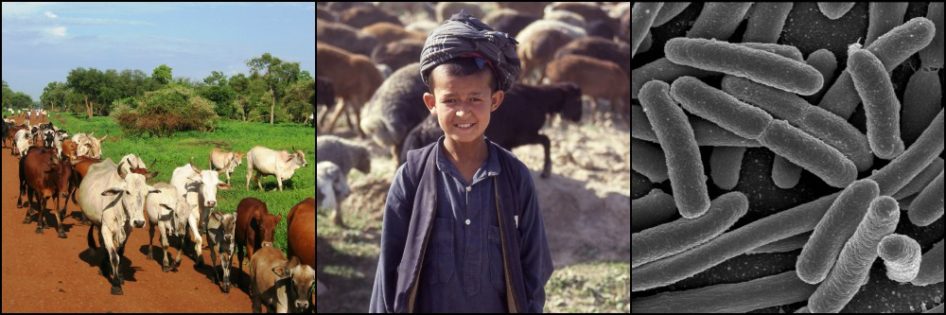

The image of cattle, goats or camels pulling the last leaves from a thorny acacia bush on the bone-dry plains of the Sahel invites the conclusion that overgrazing causes these harsh conditions. More often, however, these livestock are here as a result of the difficult conditions, but they did not cause them.

Rainfall in arid lands is insufficient to support crop farming. Instead, pastoralists bring their animals to harvest the sparse resources that are available, converting them to forms useful to people: milk, meat, hides and other animal products. Animals do not replace more productive economic activities in these arid regions; they are the only option.

In wetter areas of lower-income countries, farmers graze their livestock on communal pastures — typically unsuited to crop production — and supplement this with post-harvest crop residues that are inedible for people. In turn, the animals are used for draught power and recycle nutrients, through the use of their manure as fertilizer and trampling uneaten residues into the soil. In such mixed crop-livestock systems, animal crops do not compete with human crops; they complement each other.

This is not to say that livestock are without problems. Ruminants (including cattle, goats and sheep) produce large amounts of the potent greenhouse gas methane, and animals reared with poor nutrition and healthcare produce more methane per liter of milk or kilogram of meat than those reared under better conditions.

In some cases, livestock do contribute to environmental degradation. One example of this is the drilling of boreholes in fragile ecosystems to provide water for pastoralists’ herds. This initially attracts larger numbers of animals, but the borehole does nothing to increase vegetation and the area can quickly become overgrazed and unusable, destabilizing social, economic and political dynamics among groups using the rangeland.

Another issue is antimicrobial resistance (AMR). In many wealthier countries, this is related to the heavy use of antimicrobial medications to promote livestock productivity. Lower-income countries rarely have access to enough affordable veterinary medications to make this an issue. However, the presence of counterfeited, diluted, expired or improperly stored drugs, and a habit of under-dosing animals to save money, certainly contribute to AMR in these countries.

Despite these potential problems, livestock in lower-income areas effectively convert otherwise unusable resources to milk, meat, eggs, hides and other products that can be consumed or sold, thereby strengthening food security and livelihoods of their owners and communities.

Common livestock interventions and their pitfalls

Value chain development

Poor livestock farmers tend to be overburdened with daily labor requirements that make it impossible for them to put in the extra time and cost required for market-oriented production (e.g. more and better nutrition, healthcare, shelter, breeding management, etc.). Hay- and silage-making are good examples: their promotion frequently fails, not because farmers don’t understand the benefits or lack the technical know-how, but because they don’t have the extra time or labor needed to make them feasible.

For such farmers, focusing on techniques to improve animal survival and production (for home consumption or occasional sale) without increasing the labor or cost burden is critical to sustainable change (and can also help reduce greenhouse gas emissions). This can include identification of underutilized feed sources, biosecurity practices to limit disease outbreaks and improving access to animal health services. Village cooperatives can be another way to mitigate time constraints, such as for small-scale goat or poultry enterprises run by women.

Efforts to integrate livestock producers into value chains are often better focused on middle- and higher-income farmers. These farmers are more likely to have access to the resources necessary to improve livestock rearing and marketing to a level necessary for value chain participation. But even these must be selected carefully.

Many livestock owners, both large and small, have no interest in producing for value chains. Their animals may serve as a supplement to household diets (milk and eggs), as a coping mechanism during crises, for slaughter during celebrations, for social prestige and/or as a form of savings account for holding assets. Such farmers are not looking to maximize productivity, since they plan neither to eat nor sell these animals in the near future.

It is not easy to convince a farmer to work to put more weight on an animal they do not intend to sell. They are, however, interested in improving the survivability of their animals, which can be an alternative focus of interventions for these people.

Vaccination and deworming campaigns

Vaccinations and deworming are often the first livestock activities planned in both development and humanitarian interventions. These services are normally in short supply, so providing them can only be beneficial, right? Unfortunately, this is not always true.

Disease and parasites exist in every animal population. Their presence, however, does not necessarily mean they pose a significant problem. In the absence of vaccines and drugs, animals and pathogens often evolve a live-and-let-live arrangement in which neither significantly harms the other.

In such a situation, vaccinating a large portion of animals can disrupt this equilibrium. Pathogen numbers are greatly reduced or eliminated and new generations of animals do not have to contend with them and so waste no energy developing immune defenses against them. When the project ends and vaccinations are discontinued, the pathogen returns and the previously unexposed younger generations are now highly vulnerable to their effects. Many may die, whereas, before the vaccination campaign, they would not have even been ill.

Deworming and tick control offer a similar scenario. In addition, internal parasites and ticks are usually a problem for only a small percentage of animals in a herd, and these can benefit from treatment. But treating every animal promotes development of resistance in the parasites and is rarely, if ever, recommended.

This is not to say that vaccinations, antimicrobials and parasite control do not have a place in development and humanitarian work. But we should recognize that they are not automatically a win-win for implementors and beneficiaries. They have the potential to do good, but they can also do harm.

Animal health service delivery

Vaccines, treatments and deworming are often provided to livestock owners free of charge by project implementers. This well-intentioned strategy makes it very difficult for private veterinarians, other animal health workers and agro-vet suppliers to make a living, as demand for their services disappears in the face of these free services and products.

Despite protests, it is rare that livestock owners are unable or unwilling to pay for needed animal health services. If cash is in short supply, they will often pay in kind, contributing a goat, for example, in exchange for vaccinating the rest of their flock. Even simple cost recovery for animal health services instills a sense of value for these services in the community and makes it easier for private animal health providers to charge for their services when the project is finished.

To minimize these effects, coordination with other projects in the area ensures standard pricing. Nothing creates more distrust from communities than different NGOs charging different prices for the same services. For the poorest households that cannot contribute to the cost of animal health services, consider vouchers or some other mechanism to allow these households, and only these households, to receive free or heavily-subsidized services.

Private animal health service delivery can also be compromised when implementors train large numbers of community animal health workers. When the project ends, these health workers cannot sustain viable businesses and so turn to other income sources, wasting their extensive training. Those that persevere can flood the market and put out of business the few private animal health businesses that were active in the area before the project.

To address this, prioritize working through existing animal health workers and service providers to support their businesses and make them stronger by the end of the project, not weaker.

Breed improvement

Breeding programs are another popular intervention in livestock development. Local animal breeds are viewed as having low production potential. Introducing high-producing breeds from other countries and crossbreeding with local breeds is seen as an easy fix.

The problem is that local breeds are extremely tolerant of their environment, including high temperatures, parasites and diseases, poor nutrition and droughts. Non-native breeds and their crosses cannot support these harsh conditions without a lot of extra work and resources from their owners. Without it, these animals either die or produce even less than the breeds they were meant to replace.

In most cases, significant gains in local breed productivity can be achieved with improved feeding, health and other husbandry practices. If farmers can implement these practices and bring out the full potential for their local breeds in a sustainable manner then, and only then, consider the possible use of exotic breeds to further raise productivity.

Conclusion

Despite some environmental concerns posed by livestock rearing in low-income countries, the potential for increased animal source food consumption and income from the sale of animals and their products outweighs the disadvantages. But to be successful, livestock interventions should be thought through carefully to ensure they best meet the specific needs of the target communities, address true problems and do not create new problems.

Goats, sheep and poultry, in particular, can boost household nutrition levels and incomes and promote women’s and youth empowerment, as men tend to concentrate on larger animals such as cattle or camels. Practices that increase the labor burden on women are rarely sustained.

Do not assume that every livestock owner aspires to commercial production. There are many other, more common, uses for livestock.

Do not assume the presence of an animal disease means it is a problem. Treating or preventing such diseases can cause issues that didn’t exist before.

Livestock interventions have a time and a place in development and humanitarian work. But there is no one-size-fits-all equation. Each should be planned and implemented carefully according to the needs of the livestock owners. They know their animals and their problems better than anyone. Use their knowledge to help find solutions to the problems they define.